This week, Team BirdCast highlights a friend in the field. Today, it is Dr. Emily Cohen, a research associate at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.

“This is the time of year when the Texas coast really starts to shine” -@DrBirdCast Apr 8, 2017

A couple weeks ago I got to get out of my office at the Migratory Bird Center in DC to band birds on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. On my way down, I read the BirdCast migration forecast for the Gulf Coast: “The next frontal boundary arrives on Monday night and Tuesday, offering the best chance for western Gulf Coast fallouts and concentrations on Tuesday in particular.” Sweet, sounds good! I will be there on Tuesday! Spring migration is my favorite season of the year- when our migratory birds make their spectacular journeys and return up North.

Our collaborator, Andrew Farnsworth from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and his colleagues Benjamin Van Doren at the Edward Grey Institute and Kyle Horton at the University of Oklahoma have been analyzing big data – weather surveillance radar and eBird data, to be specific – to make regional migration forecasts, or “Birdcasts” in real time. If you have not been following the weekly BirdCast reports this spring, you should check them out! You are already on the website! (Twitter: @DrBirdCast).

Clive Runnells Mad Island Marsh Preserve, Matagorda County, TX

A day after a weather front is when we catch the most migrants at our mid-TX coastal banding station. Many birds arrive across the Gulf and, if they encounter unfavorable north winds or weather, they often stop in the first forested coastal habitat. That’s us! Unfortunately, it’s usually not safe for us to open nets when there are strong north winds – conditions best for migrants stopping. But the nocturnal migrants often do not leave the night after a storm. Our site is busiest the morning after a coastal storm front.

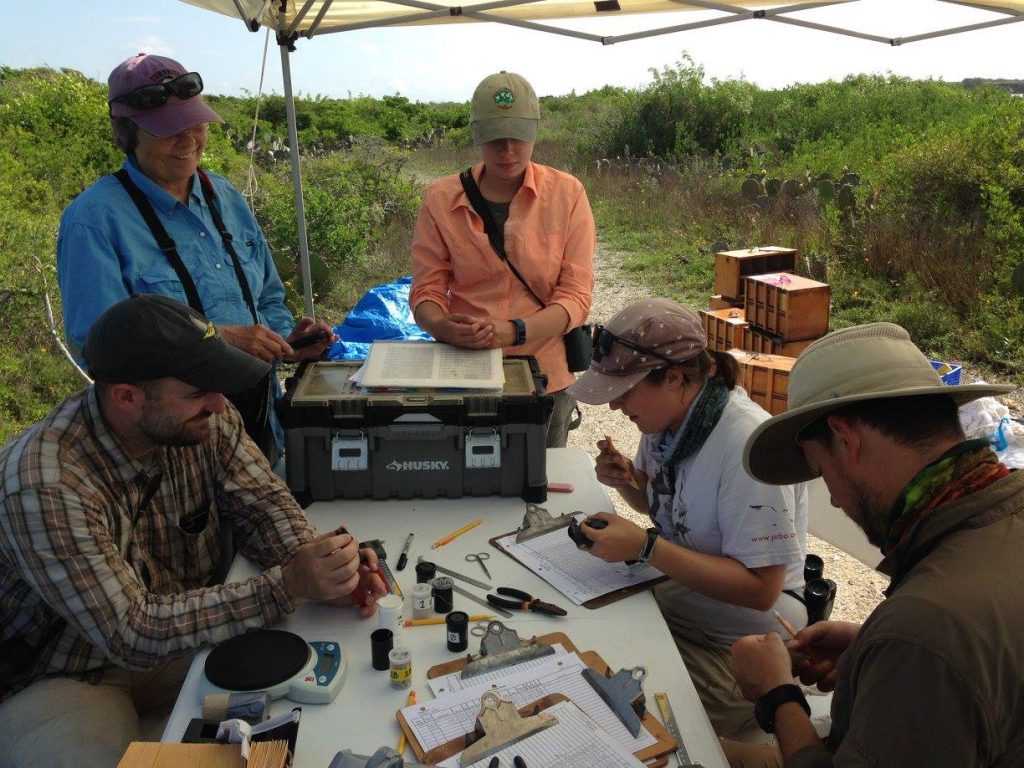

And Tuesday was our biggest day yet! We banded about 75 individuals of 25 different species. It was fun. On my net run, I caught a glowing tomato-red scarlet tanager, the red contrasting with the glossy black wings. Yellow and black Hooded and Kentucky warblers. Bright blue Indigo buntings. Amazing to think that these bright little animals just flew 15+ hours non-stop across the open waters of the Gulf of Mexico! We catch them in nets, place a unique band on one leg, make some measurements, keep a feather for later analysis, and let them go to continue their journey north. Good luck guys!

The banding crew: Tim Guida, Bea Harrison, Allison Huysman, Danielle Aube, and Josh Haughawout.

Kentucky Warbler. Lauren diBiccari.

Scarlet Tanager. Emily Cohen.

Hooded Warbler. Kristin Davis.

Indigo Bunting. Kevin Bennett.

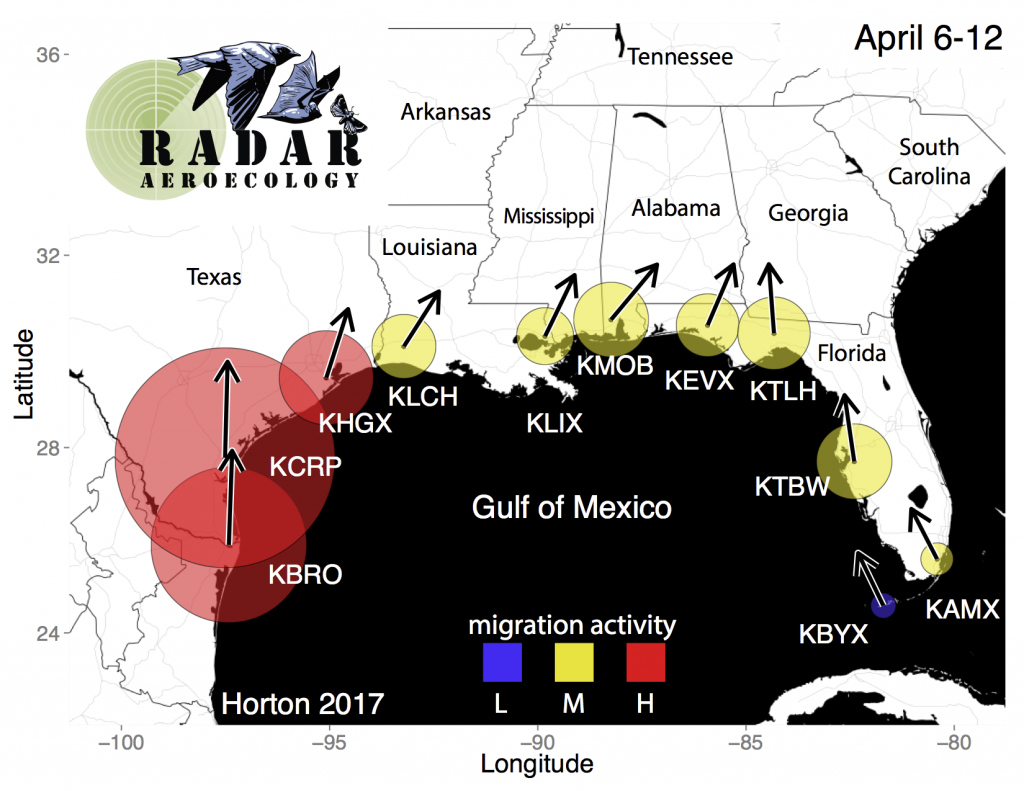

Most information about migrant passage and habitat use has come from single sites. This on-the-ground information about migration is invaluable and not easy to collect. Still, we need Gulf-wide information about the distributions of migrants to be able to identify key stopover habitat and airspace corridors necessary to conserve migrants moving through this critical region. For example, see Kyle Horton’s (@Kyle__Horton) weekly maps of the mean intensity and direction of bird movement through the airspace around the Gulf of Mexico as presented by BirdCast:

Weekly mean spring nocturnal migration activity and direction of movement in the Gulf of Mexico region for the week of 6-12 April, 1995 to 2015. Circular buffers around radar stations represent migration activity scaled to radar reflectivity (a measure of biological activity), with weekly activity represented by size scaled to the activity at KCRP Corpus Christi and seasonal activity represented by colors scaled to the most intense movements of the spring period (L: light, M: moderate, H:heavy); arrows represent mean track direction (a measure of the direction birds are traveling) derived from radial velocity.

These maps show us the nocturnal movement through the airspace; they don’t necessarily tell us where birds land, or what is happening on the ground right now. That’s where the banding comes in. We usually band more birds when more are passing over. So, where are they? We are having a really slow April. Plus, we are catching bird species now that we usually catch two weeks earlier. I was just texting with Mariamar Gutierrez, who is running a banding station near Apalachicola Florida for the Gerson lab (@Umass_birdphys) at UMASS Amherst, and she said the same thing. They aren’t catching their usual numbers of migrants and have entirely missed many of the early species, including Prothonotary and Hooded Warblers. Why not? Should we be worried? It’s hard to say for sure but probably not. As the BirdCast forecasts are showing, most migrants are likely riding the favorable south winds and skipping the coast right now. Plus, people are also reporting to eBird that they are seeing these species further north (submit your sightings here). Still, it looks like a late year for some spring migrants.

Most annual mortality occurs during these migratory journeys and the majority of our migratory bird species are declining. So, now is the time to draw syntheses from all available data sources to understand the habitats and threats that birds encounter both in the air and on the ground during migration. We are working on that. With support from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Coast Conservation Grants Program, in partnership with Southern Company, we are working together to map and link stopover and airspace habitat around the entire Gulf coast from the Keys in Florida to Brownsville, Texas. Together with Andrew Farnsworth’s group at Cornell Lab of Ornithology and his collaborators at Oxford and the University of Oklahoma (@DrBirdCast, @EGIOxford, @Aero_Eco), and Jeff Buler’s lab at University of Delaware (@J_Buler), we are mapping the Gulf-wide distributions of migrants in airspace and stopover habitat. With weather radar, we can take a comprehensive look at how winds and weather influence where birds are on the ground and in the air- and link the two together.

Stay tuned!

Emily Cohen

(@SMBC @Emily_B_Cohen)