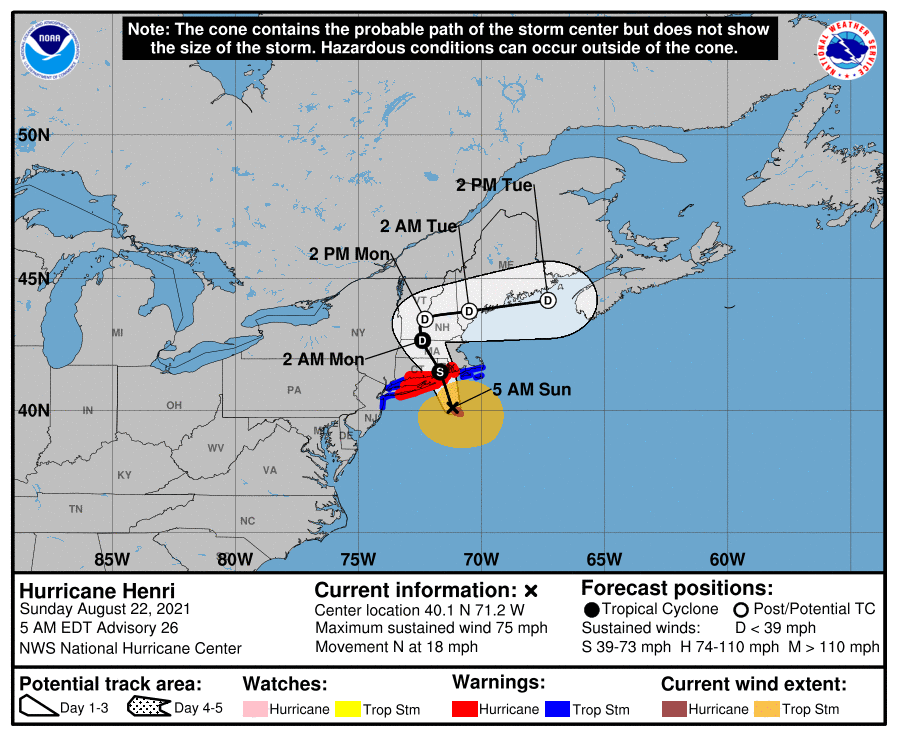

Updated on Sunday 22 August, 7am ET. Tropical Storm/Hurricane Henri is forecast to make landfall in eastern Connecticut or Rhode Island with dangerous storm surges, strong winds, and heavy rainfall. The storm is then slated to move up the Connecticut River valley before departing east into the Gulf of Maine.

With safety as the absolute highest priority, and a healthy respect for the dangers of tropical systems, the BirdCast team would like to highlight some attributes of this storm that will increase the likelihood for deposits of pelagic species in southern New England (and portions of Long Island, especially eastern Long Island):

With safety as the absolute highest priority, and a healthy respect for the dangers of tropical systems, the BirdCast team would like to highlight some attributes of this storm that will increase the likelihood for deposits of pelagic species in southern New England (and portions of Long Island, especially eastern Long Island):

- This storm has not traveled over land prior to its predicted landfall, making it one of the few storms in recent memory that has arrived to the region directly from the ocean. In all likelihood, all birds entrained in the circulation of this system will therefore arrive with the storm, unlike previous recent tropical systems arriving in the region after traversing lands farther south, in the mid Atlantic or Carolina regions.

- This storm is passing through an area at the right time to entrain large numbers of seabirds (e.g. from the Gulf Stream), especially well-characterized this year by several recent boat surveys including these that highlight Black-capped Petrel, White-faced Storm-Petrel, Audubon’s Shearwater, White-tailed Tropicbird, Band-rumped Storm-Petrel, and numerous other species.

- The storm’s speed over the water (rapid forward movement) and predicted path after landfall (moving up the Connecticut River valley, into New England, and then to points east en route to the Gulf of Maine), highlight many areas where entrained and displaced birds could be deposited (i.e. there is much coastline and there are many water bodies and river valleys east of the storm’s track to collect birds).

For this storm we expect that Black-capped Petrels, as well as Band-rumped Petrels, may compose a significant portion of inland observations of entrained and displaced birds. So, too, we expect potential, given the numbers of such species offshore presently, for White-tailed Tropicbird, White-faced Storm-Petrel, Audubon’s Shearwaters, Sooty and Bridled Terns, and other species to occur. Areas of eastern Long Island, eastern Connecticut, and central and eastern Massachusetts will experience the greatest fallouts from the storm’s passage beginning Sunday and continuing into Monday. Southern Vermont, New Hampshire, and eventually even Maine may experience some of this fallout, as well, later on Monday and Tuesday; however, much of the storm’s avian cargo will be long downed in the initial 36 hours after landfall.

Please follow along on this live map to see where hurricane-driven species occur.

Although we cannot overemphasize the need to prioritize safety above all else, we can highlight some consideration if you can bird safely without harm to yourself or to those around you. Please see this recapitulation below of accounts from Hurricane Irene in late August 2011.

HURRICANE BIRDING — AN eBIRD PRIMER

SAFETY FIRST!

To reiterate, remember that hurricanes are devastating and dangerous events. Driving in rain is bad enough, but driving in rain and hurricane force winds can be deadly. Avoid crossing bridges in high winds. Downed trees and powerlines, blowing debris, and other dangers only add to the peril.

Storm surge flooding is perhaps the most dangerous aspect of such storms. Since a surge of 15 ft or more can occur, many otherwise “safe” areas might be deadly in a hurricane. Do not take any chances with driving through flooded areas and do not do anything that might trap you in a low-lying area that is being flooded, either coastally or inland (where rivers can rise up VERY fast in precipitation from hurricanes). After Hurricane Irene in 2011, the Hudson River had so much flow that major bridges at I-90 and I-84 were closed for 2 days, seriously disrupting regional travel.

If you are considering looking for birds before or after the storm, make sure you are being safe during the storm’s passage. Don’t even consider intentionally putting yourself in the center of the strongest part of the storm.

SHELTER

Whether birding in the advancing storm or after the passage of the storm, you will need shelter from both wind and rain. If you plan any birding in the storm, think hard about what sites (overhangs on buildings, hotels with rooms facing the lake, river, or ocean, etc.) will provide shelter for you and your optics and not be facing directly into the expected wind direction. Birding from your car can sometimes be effective and safe, since an open car window facing away from the wind can be quite effective. Think in advance about how to use your telescope, either on a tripod or a window mount, from inside your car. Bring paper towels to dry off wet optics!

WEATHER

Understanding hurricanes is important. Hurricanes are cyclonic, so the winds are rotating counter-clockwise in the northern hemisphere. This means that northeast quadrant of an advancing storm will have winds from the southeast, and that those winds will shift to become southwesterly as the storm center passes to the west. That wind shift is perhaps the key moment to be ready for and watch carefully for birds. Some of the best rarities have dropped right out of the sky at this moment when winds shift from S or SE to N or NW. This is important to understand since seabirds that do not like to fly over land may be ‘pinned’ against shorelines in the high winds of a hurricane. As the storm passes, you may want to shift your strategy, and be sure to consider shifting winds as you do so. Also remember that the northeastern quadrant of the storm has the strongest and most dangerous winds as well as the most rain. After the storm passes, conditions can quickly clear up and visibility can be excellent.

BIRDS IN THE STORM

One important general pattern is that the eastern sides of hurricanes tend to have higher loads of displaced birds than the western side. This could be because the tighter isobars here keep birds more effectively entrained within the storm. But note that in Hurricane Bob 1991 most rarities in New England were along the path of the eye (the area east of the storm was out to sea though!)

Numerous reports also refer to birds being ‘trapped’ within the eye of storms, and many observers have seen large numbers of rarities in the calm eye of storms, although we would NEVER recommend intentionally putting yourself in the path of a hurricane with a well-defined eye (these tend to be stronger storms). The eye of a storm tends to fall apart in the Northeast US, but the dissipating eye and clear areas between rain bands surely “hold” birds too.

One consideration is how birds will behave in relation to obstructions. Most displaced birds will want to stay over water if possible, but tubenoses may be more closely tied to water than terns, for example. At a given reservoir a shearwater, storm-petrel, or even Pterodroma petrel is likely to stay for the day, maybe departing overnight. But terns, gulls, and shorebirds may depart if the weather allows; your exciting Sooty Tern may pick up and fly over the treeline and away. Note also that certain seabirds, especially boobies and gannets, shearwaters, and Pterodroma petrels, seem to avoid crossing bridges. There are several indications that birds like this may feel ‘trapped’ on a given side of a bridge and unwilling to fly under one. This could be a factor as you plan where to check for birds.

Hurricane strength obviously has a bearing on how many birds are displaced, and roughly speaking, stronger storms carry more birds than weaker ones. However, strong hurricanes that dissipate to Tropical Storms can still carry birds long distances, ESPECIALLY if that dissipation occurs after the storm makes landfall. Storms that weaken to Tropical Storms while still at sea typically carry surprisingly few displaced seabirds; storms that make landfall as a strong Tropical Storm or Hurricane almost always displace some birds inland.

SITES TO LOOK FOR BIRDS

Hurricanes and birding them can be grouped in three phases. For any plans you make, think carefully about your local area and how birds may behave in each of these three storm phases.

Phase 1: Before the storm

An advancing hurricane will have a large front of winds blowing from the southeast in its northeast quadrant. If birding before the storm, pick a site where southeasterly winds will pin birds against the shoreline, or better yet, concentrate them in a bay or river mouth. Watch for storm birds flying from south to north with the winds at their backs. Often the local birds may be flying any which way, but the interesting storm birds will be heading up from the south fleeing the path of the encroaching storm. Sometimes rarities like Sooty Terns can fall out at inland lakes with the storm center still many hundreds of miles to the south. For example, Sooty Terns turned up at an inland lake in Maryland at 2pm on Friday, 6 September 1996, while the storm center of Hurricane Fran was still south of Cape Hatteras. It pays to get out and try, but do so safely and beware the storm surge and encroaching storm.

Phase 2: During the storm

Birds can be anywhere. Check any spot with water, especially rivers, large lakes, or inland bays. even small lakes, ponds, or wet fields can generate exciting birds, especially shorebirds. If you can’t get to water, just look up. Some lucky birders have picked up Sooty Terns and other surprises right over city rooftops with no water in sight! Try to get a look at any grounded bird that a friend or relative reports to you and make contact with rehab centers that might receive and rehabilitate rare birds.

Phase 3: After the storm

It can often be difficult to connect with displaced seabirds after the passage of the storm. Check lakes for rare seabirds that may feel “trapped” on the lake until nightfall. Check rivers and coastal bays for birds reorienting back to saltwater, especially the eastern sides if westerly winds are ‘pinning’ birds to a given shoreline. Theoretically, there could be several days worth of commuting rare birds along major rivers like the Hudson and Connecticut Rivers.

Be alert for any sick, dead, or dying birds, since these could represent rarities. Check known shorebird spots, tern concentration spots, gull roosts, etc to see if any rarities have stopped for a rest. Bays behind barrier islands can often trap seabirds just after a storm, and often the seabirds will also feel trapped by bridges. If there is a route back to the ocean, they may eventually find it, but many tubenoses (e.g., shearwaters and storm-petrels) might feel ‘stuck’ in a barrier island bay even if the ocean is just 200m away if they simply flew over the narrow strip of land.

Usually most rarities occur within a few hours or at most a day of the storm’s passage. Only on very rare occasion do species like Sooty Terns or tubenoses occur longer than 24 hours after a storms passage, and many seem to leave overnight. Very large lakes, especially the Great Lakes, can sometimes hold rarities for up to a week though, so be sure to get out birding as much as you can after a storm and see what is about. Frigatebirds in particular are famous for occurring well before and well after storm passage.