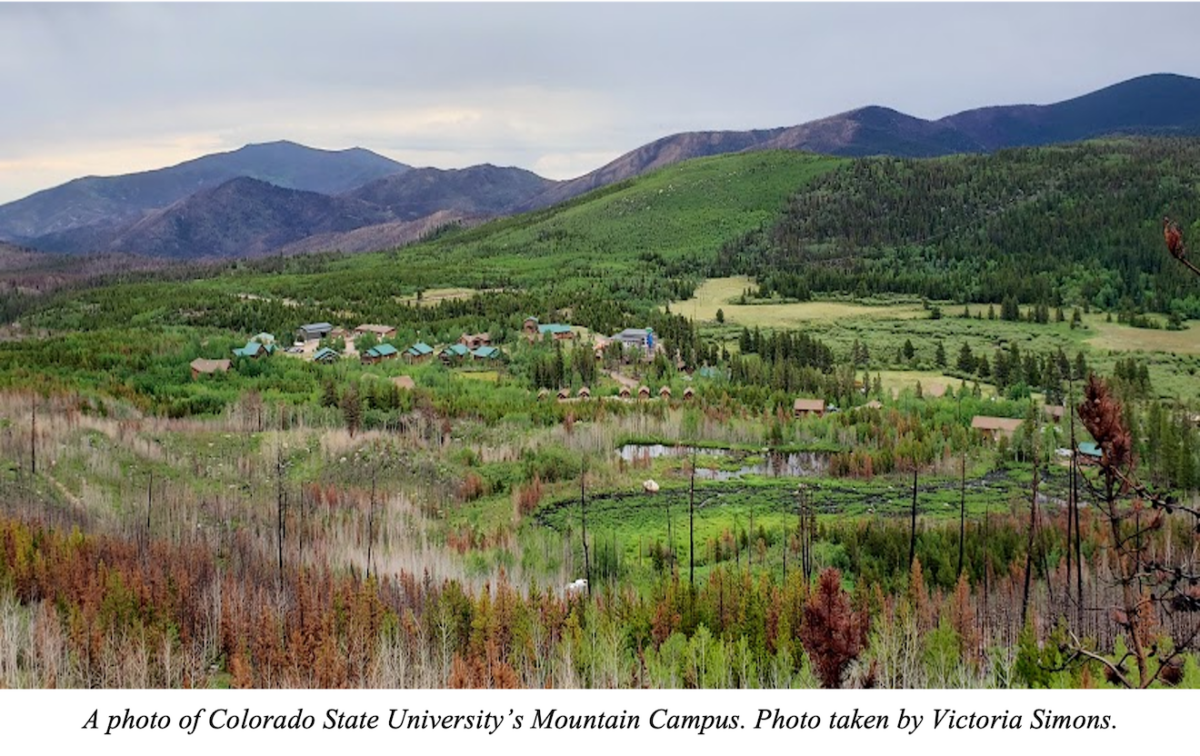

I sit on a secluded bench to take in the mid July views of Colorado State University’s Mountain Campus at Pingree Park, a remote site dedicated to field courses, conference retreats, and mountain research. As the evening sun bathes the valley in its warm, golden light, a gentle breeze carries calls of Ruby-crowned Kinglets, Wilson’s Snipe, and Mountain Chickadees to where I sit. I watch as a bull moose emerges from the willow and makes its way across the colorful sea of wildflowers, eventually disappearing into the distant pines. This evening’s calm is a stark contrast from the hectic morning of fieldwork, but even at this hour, I still see several Tree Swallows deftly maneuvering through the air and swooping over the river as they forage for insects. Unlike me, they don’t have any time to relax.

Tree Swallows belong to a guild of birds known as aerial insectivores, a group that forages for insects while in flight. In late spring, foraging intensifies as adults provide for a nest full of growing chicks. Insect availability is dependent on conditions in the airspace – a vast area of habitat that is central to the field of aeroecology. While recognition of the lower atmosphere’s biological importance is growing, the area remains critically understudied. That gap in our knowledge is what brings me to the Mountain Campus: to study how Tree Swallow foraging behavior relates to their usage of airspace as habitat.

A photo of Victoria Simons banding an adult female Tree Swallow. Photo taken by Annika Abbott.

Today was a typical workday for Annika, my field technician, and I. We started off the morning at 7 a.m. by sneaking up to occupied nest boxes, covering the entrance hole, and capturing the female through a side door as she incubated her eggs*. Some individuals were cooperative, while others indignantly squawked as they were carefully removed, weighed, and measured. I also fit each female with a passive integrated transmitter (PIT) tag on the left leg before release, watching their iridescent blue feathers catching the sunlight as they flew out of sight.

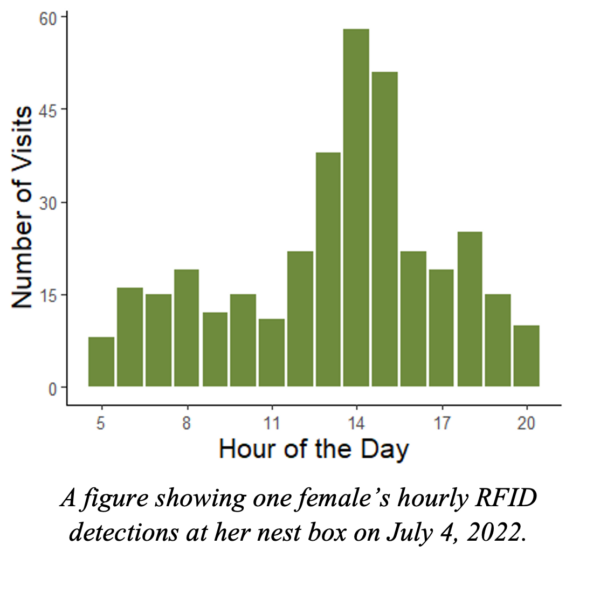

With help from Dr. Eli Bridge, a biologist and professor at the University of Oklahoma, I programmed radio-frequency identification (RFID) readers to detect each of the 22 deployed PIT tags throughout the breeding season. A receiving antenna mounted around the entrance to each active nest box recorded the time and unique ID anytime a tagged female entered or exited the box, cataloging over 450 detections per day during the period of peak nestling growth. From these data, I will be able to get a sense of parental provisioning effort. Combined with monitoring nestling growth and development, I hope to tease apart how parental foraging behavior affects nest success, especially when considering responses to weather conditions and aerial insect abundance. To assist with this, the BirdScan MR1 has been deployed in the valley nearby. This mobile radar detects biological activity of birds, bats, and insects in the airspace, using measures of reflectivity from wingbeats to categorize each organism accordingly. In this case, the data will be used to quantify aerial insect abundance, giving insight to how food availability changes with weather conditions.

A photo of Victoria Simons holding a brood of Tree Swallow nestlings. Photo taken by Annika Abbott.

Although this is the third year I’ve spent working with Tree Swallows, I still find myself amazed over the feats these small birds accomplish every summer. After a long spring migration, they somehow muster up enough energy to construct extravagant, feather-lined nests, lay several pale pink eggs, and provide for a brood of hungry nestlings. It’s hard to imagine that such a seemingly tough species could be experiencing drastic population declines, but especially considering the shifting climate, they are facing bigger threats than ever before. Unpredictable weather and the subsequent reduction in insect abundance is just one example of the many challenges these birds must overcome. With a deeper exploration of airspace habitat, we may be able to gain critical insight into not only the behaviors of Tree Swallows, but aerial insectivores as a whole. The more we understand about these birds, the better able we will be to lend them a helping hand when they need it most.

*All birds were handled under necessary university, state, and federal licenses and approvals.