Purple Gallinules are well known as champions of long-distance vagrancy, with records from as far north as Iceland, as far south as South Georgia Island, as far west as the Galapagos Islands, and as far east as Italy and South Africa (West and Hess 2002). This species, and many other rails, are habitat-based dispersalists, adapted to respond to ephemeral habitats and with the machinery to travel long distances.

Vagrant hunters on an island vagrant trap off Massachusetts checked a small marsh specifically for Purple Gallinule in October 2011 and surprised themselves by finding this one! Photo by Ryan Schain

In late fall 2013 and winter 2014 there have been a surprising number of observations and specimens collected of this species far out of range (originally compiled by our friend Louis Bevier and subsequently amended by Teams BirdCast and eBird): 7-11 November 2013, Parque Florestal Monsanto in Lisbon, Portugal (taken in to care 11 Nov and died 13 Nov); 17 November 2013, Seal Island NWR, Maine fide Juanita Roushdy and John Drury; 8 December 2013, Clarenville, Newfoundland; 8 January 2014, Trenton, Maine, thanks to Michael Good; 9 January 2014, Clermont, NJ; 10 and 13 January 2014 from Bermuda; 19 January 2014, Maccallum, Newfoundland fide Bruce Mactavish; 21 January from Bermuda; 29 January 2014, Kettle Cove, Maine (apparently long-dead) fide Richard Jones via George Armistead; 30 January 2014, Iceland; and 2 February 2014, Mullett peninsula, County Mayo, Ireland. That’s 11 far-flung records of birds that were found (Purple Gallinules are not easy to find!), with three of them crossing the Atlantic!

December to March records of vagrancy in this species are not unprecedented, but they do fall outside the more typical pattern of the species’s out of range movements. Most records in the Northern Hemisphere occur from April to November, with marked peaks matching migration periods in April-June and October and November. In the Southern Hemisphere, movements are a bit less well known, and perhaps, confounded by North American wintering birds, residents, and Austral migrants; but vagrants to South Africa and to South Atlantic islands clump between April and August.

Winter range

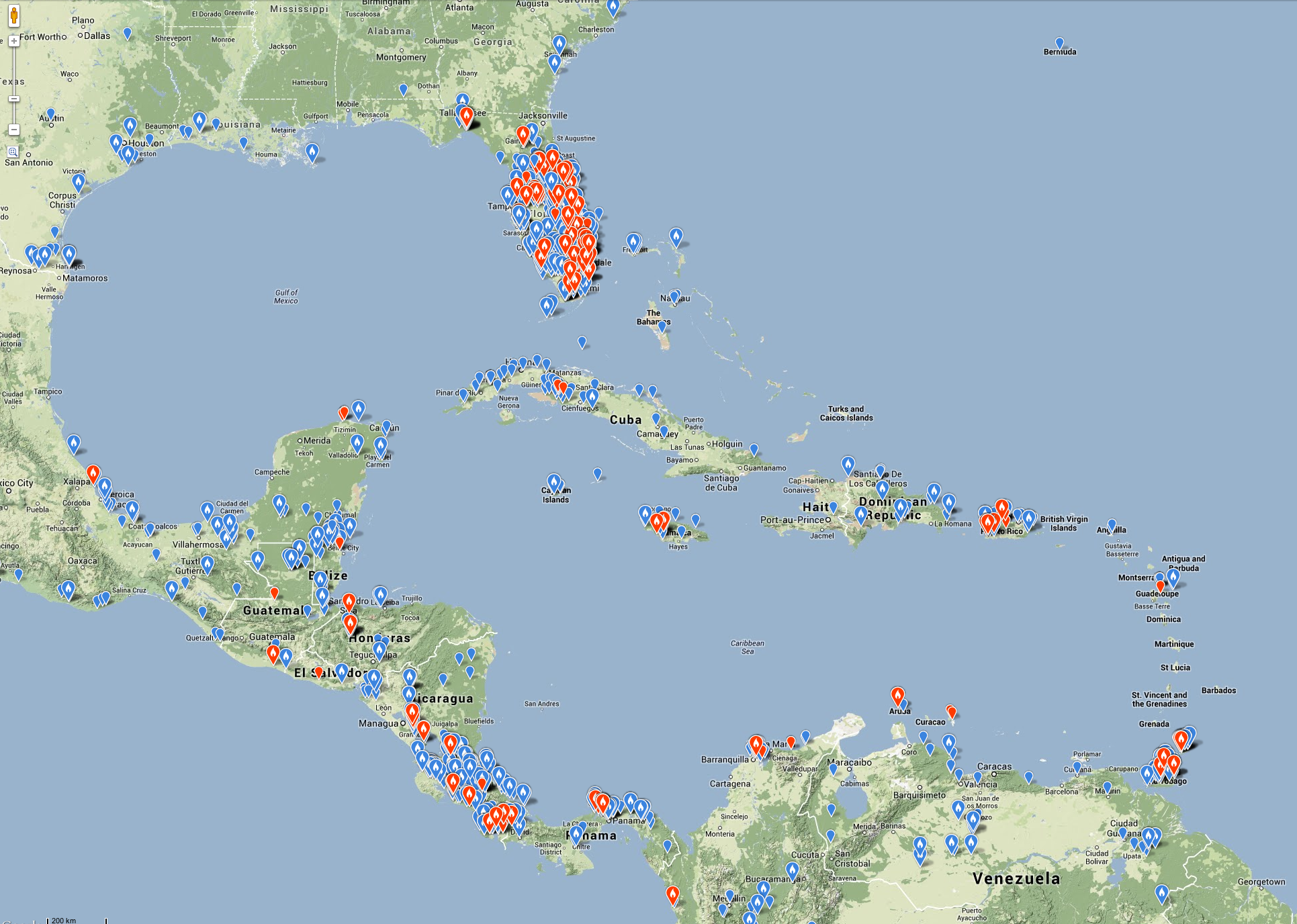

The temperate zone winter range for Purple Gallinule is primarily peninsular Florida, Mexico and Central America south to northern South America, and the Caribbean, with additional populations farther south in South America breeding during this time. The map below shows this typical distribution in eBird observations of the species from November to February. Of note in this map are occasional winter records away from Florida in the US and frequent records of the species from central Florida south to the Florida Keys. The orange balloons represent observations in the last two weeks of January 2014.

This range is by no means static, as marsh habitats with floating and emergent vegetation are often ephemeral of subject to drying out. During abnormally dry years birds may be forced to move, and this could also happen in abnormal cold years. During these movements individuals may go far afield in search of suitable habitat, a behavior that is likely echoed in numerous other species of rails. For winter 2013-2014, we contemplate the source region for this recent vagrancy event and explore hypotheses of what might be driving this year’s movement.

This range is by no means static, as marsh habitats with floating and emergent vegetation are often ephemeral of subject to drying out. During abnormally dry years birds may be forced to move, and this could also happen in abnormal cold years. During these movements individuals may go far afield in search of suitable habitat, a behavior that is likely echoed in numerous other species of rails. For winter 2013-2014, we contemplate the source region for this recent vagrancy event and explore hypotheses of what might be driving this year’s movement.

Motivation: Effects of cold?

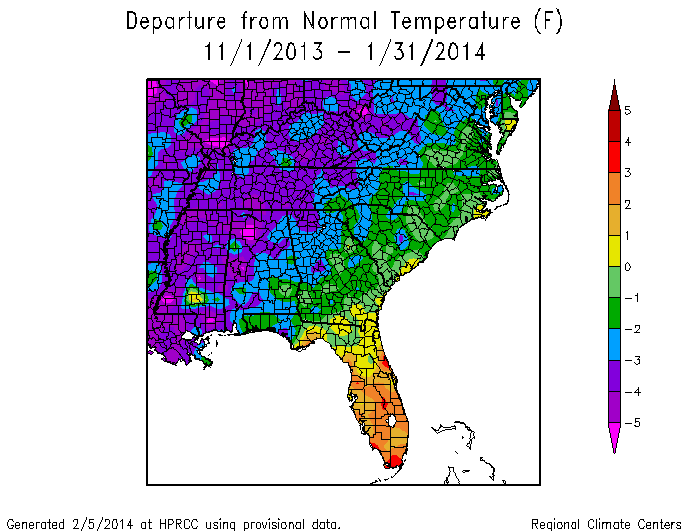

Given the media popularity of discussing the “polar vortex” in January 2014, and the record cold temperatures these arctic blasts brought to some portions of the US, freezing or abnormally cold conditions might be implicated in these Purple Gallinule movements. However, the normal winter range for this species is central and southern Florida, we believe we would need to see substantially colder than normal temperatures in Florida in November, December and January to consider Florida as the source of these strays. We do not see this pattern this year: in fact, Florida has seen average to abnormally warm temperatures.

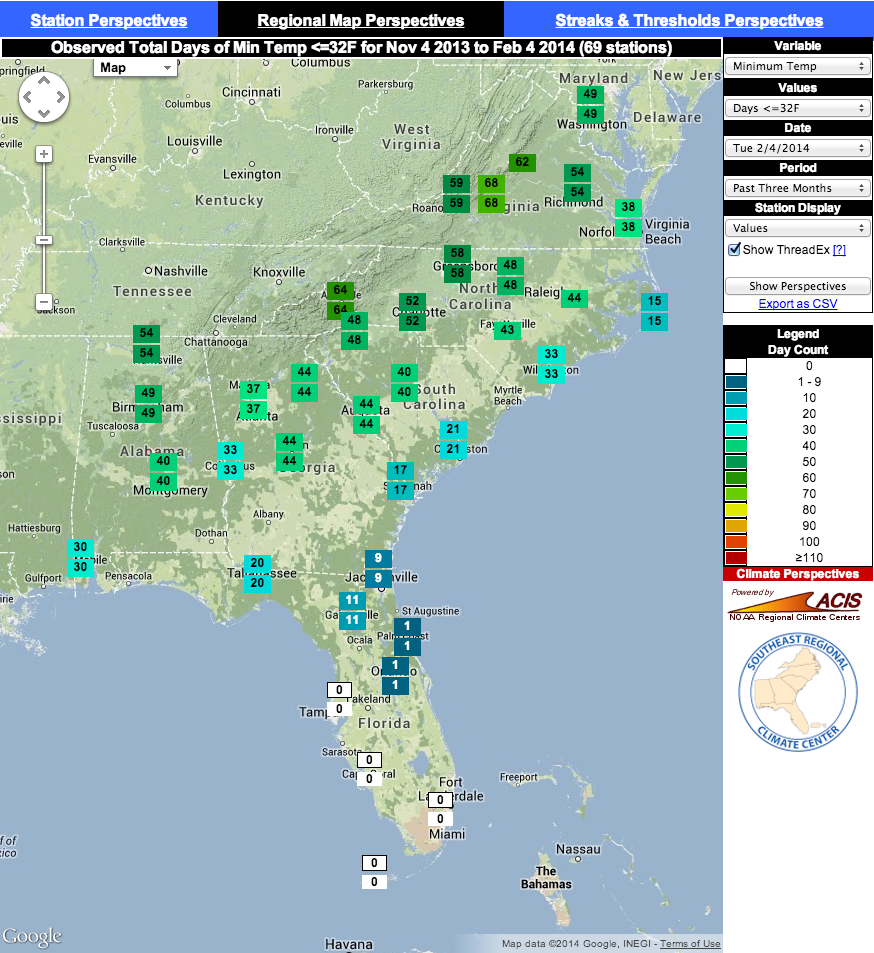

Furthermore, there have been virtually no freezes, prolonged or isolated, in the species’s typical winter range on the Florida Peninsula. Unlike areas in the Southeast US north of Florida, only 1 day since 4 November 2013 has seen temperatures dip below 0 degrees Celsius in central Florida, with no days below freezing in the heart of their Florida range.

Furthermore, there have been virtually no freezes, prolonged or isolated, in the species’s typical winter range on the Florida Peninsula. Unlike areas in the Southeast US north of Florida, only 1 day since 4 November 2013 has seen temperatures dip below 0 degrees Celsius in central Florida, with no days below freezing in the heart of their Florida range.

It would appear that neither prolonged cold nor a strong isolated freezing event are compelling explanations for conditions that would send Purple Gallinules fleeing from these Florida locations.

It would appear that neither prolonged cold nor a strong isolated freezing event are compelling explanations for conditions that would send Purple Gallinules fleeing from these Florida locations.

Importantly, we base this partly on the assumption that numbers of Purple Gallinules attempting to overwinter in coastal Georgia and the Carolinas would be too low to account for all these records. Obviously the detection rate of rallids by birders almost always underestimates their true levels of occurrence. If anyone can defend the notion that hundreds of Purple Gallinules are overwintering in Atlantic coast marshes north of Florida, we’d love to hear about it (and we would love to have your observations in eBird!)!

Motivation: Effects of drought

If cold conditions are not responsible, might drought conditions be a suitable explanation? Purple Gallinule has specific habitat constraints that are tied closely to changeable water level conditions. Late fall and early winter have been abnormally dry in Florida this year. The maps below depict an average November on much of the Peninsula, and a substantially drier December.

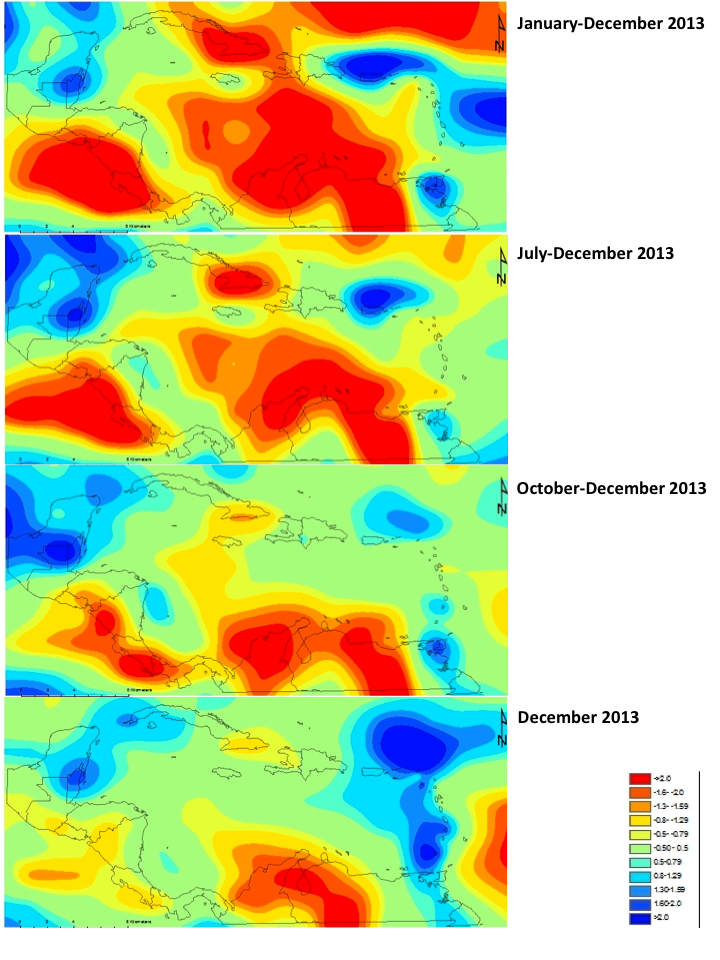

Perhaps more striking is the extent drought conditions in parts of the Caribbean. The graphic below shows the standardized precipitation indices for the the last 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month periods for southeastern Mexico and Central America, the Caribbean, and north South America. Note the striking red colors that become more intense over the course of the last year in the Greater Antilles, where Purple Gallinule winters regularly.

Perhaps more striking is the extent drought conditions in parts of the Caribbean. The graphic below shows the standardized precipitation indices for the the last 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month periods for southeastern Mexico and Central America, the Caribbean, and north South America. Note the striking red colors that become more intense over the course of the last year in the Greater Antilles, where Purple Gallinule winters regularly.  These colors represent precipitation indices 2 standard deviations below the mean for the past 30 years, indicating significant drought conditions. The potential for these conditions to spawn movements of gallinules seems very high. We believe that the vagrant gallinules probably originated here: this is an area with wintering Purple Gallinules, the conditions are ideal to spawn a large-scale dispersal event, and as we will see, the wind currents can easily connect vagrant records back to this region.

These colors represent precipitation indices 2 standard deviations below the mean for the past 30 years, indicating significant drought conditions. The potential for these conditions to spawn movements of gallinules seems very high. We believe that the vagrant gallinules probably originated here: this is an area with wintering Purple Gallinules, the conditions are ideal to spawn a large-scale dispersal event, and as we will see, the wind currents can easily connect vagrant records back to this region.

Wind and air parcel analyses explain vagrant records

Birds obviously have wings, and use them, and rallids are clearly no exception. Numerous accounts describe how rails are counterintuitively strong fliers, but of particular relevance to this discussion is this description from the Birds of North America species account:

“Though of weak-winged appearance when flying just over marsh vegetation, flies strongly when migrating, flying high and advancing in a direct course by continued flapping (Audubon 1838, Bent 1926). Migrants meeting cyclonic storms especially prone to being blown well beyond normal range. Thus low-pressure systems moving north up East Coast of U.S. carry this species almost annually to Bermuda and New England (Nisbet 1960).”

While we assume that Purple Gallinules dispersing from the Greater Antilles are likely to head in “safe” directions towards other islands, towards South America, or even back north to Florida, we also believe that any dispersal event from offshore islands will involve a percentage of birds that err off course. Once unintentionally over open-water, it also seems likely that many species of birds simply fly downwind if they aren’t already oriented towards an island or other land mass. If some gallinules ended up north and east of the Greater Antilles, we can look for wind patterns that might carry those birds up the Atlantic Coast to Canada and even across the Atlantic Ocean to Iceland, Ireland, and Portugal.

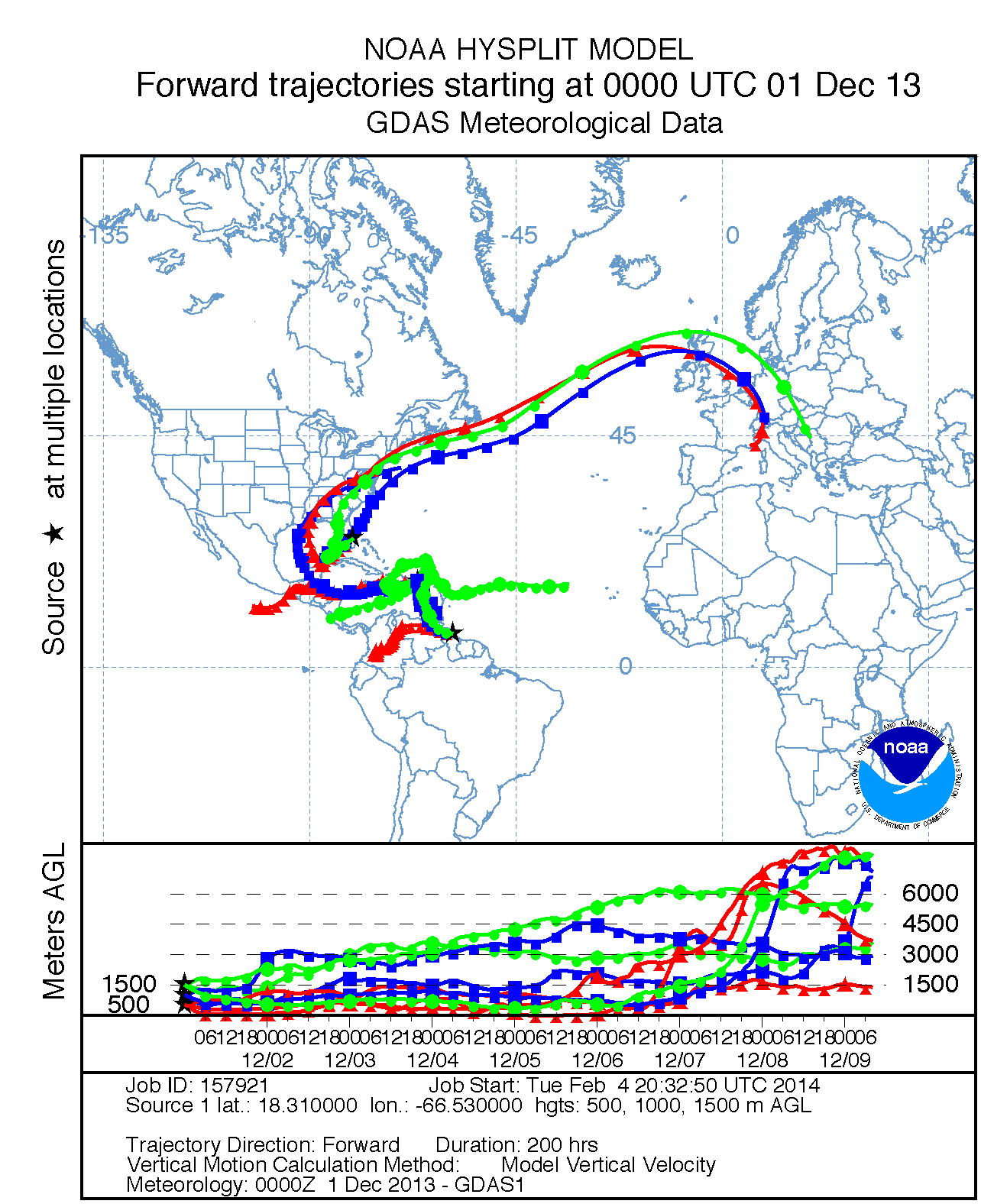

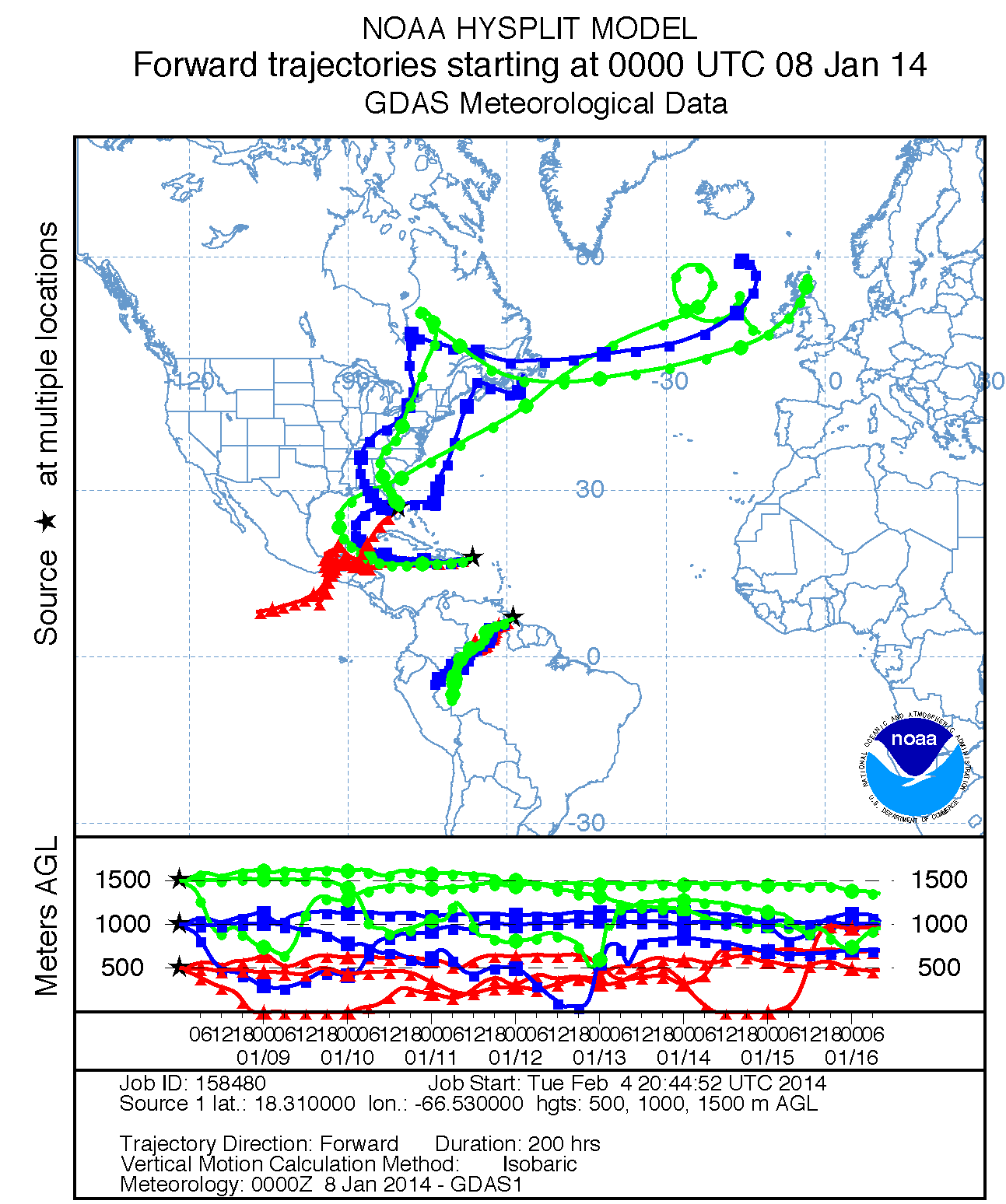

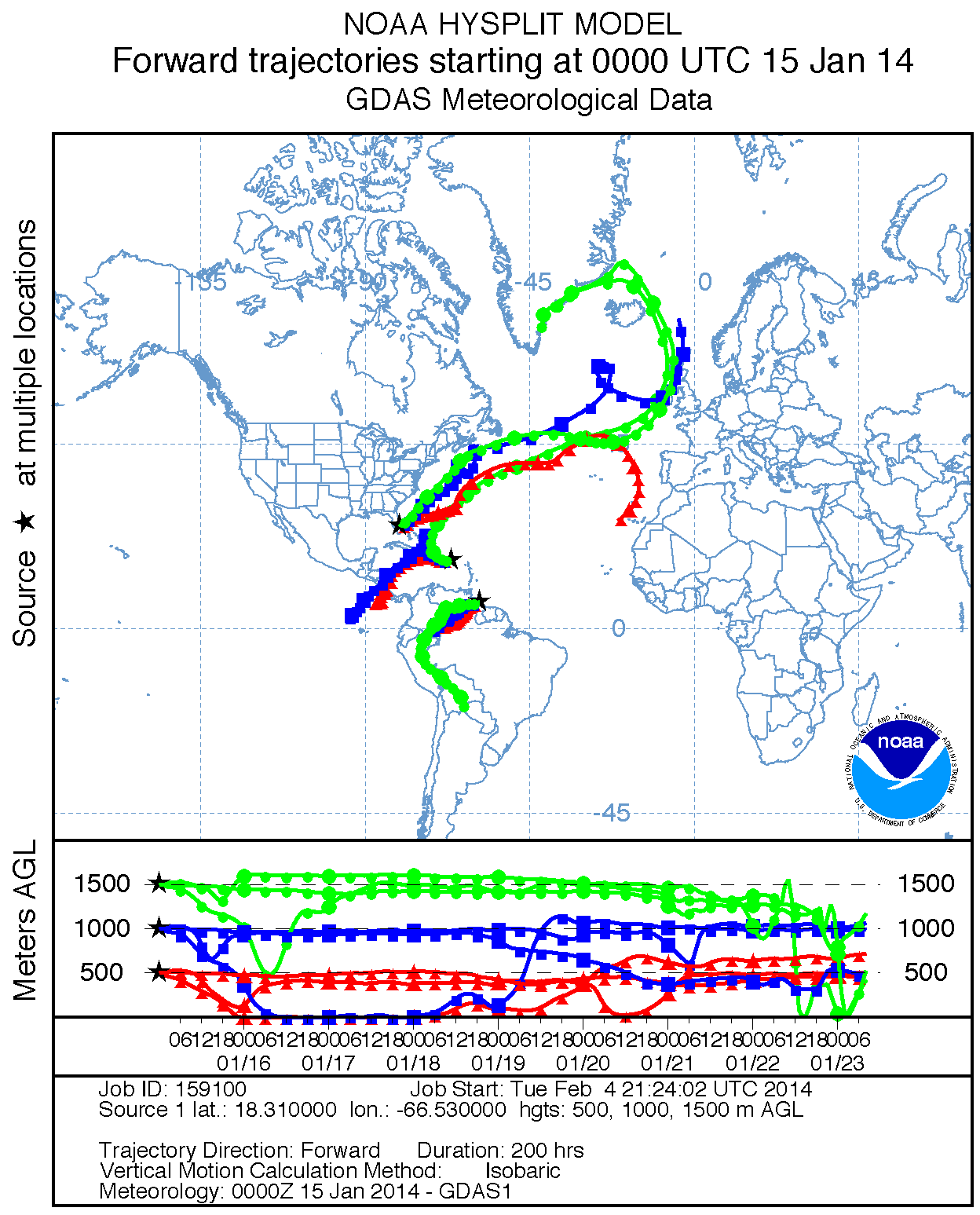

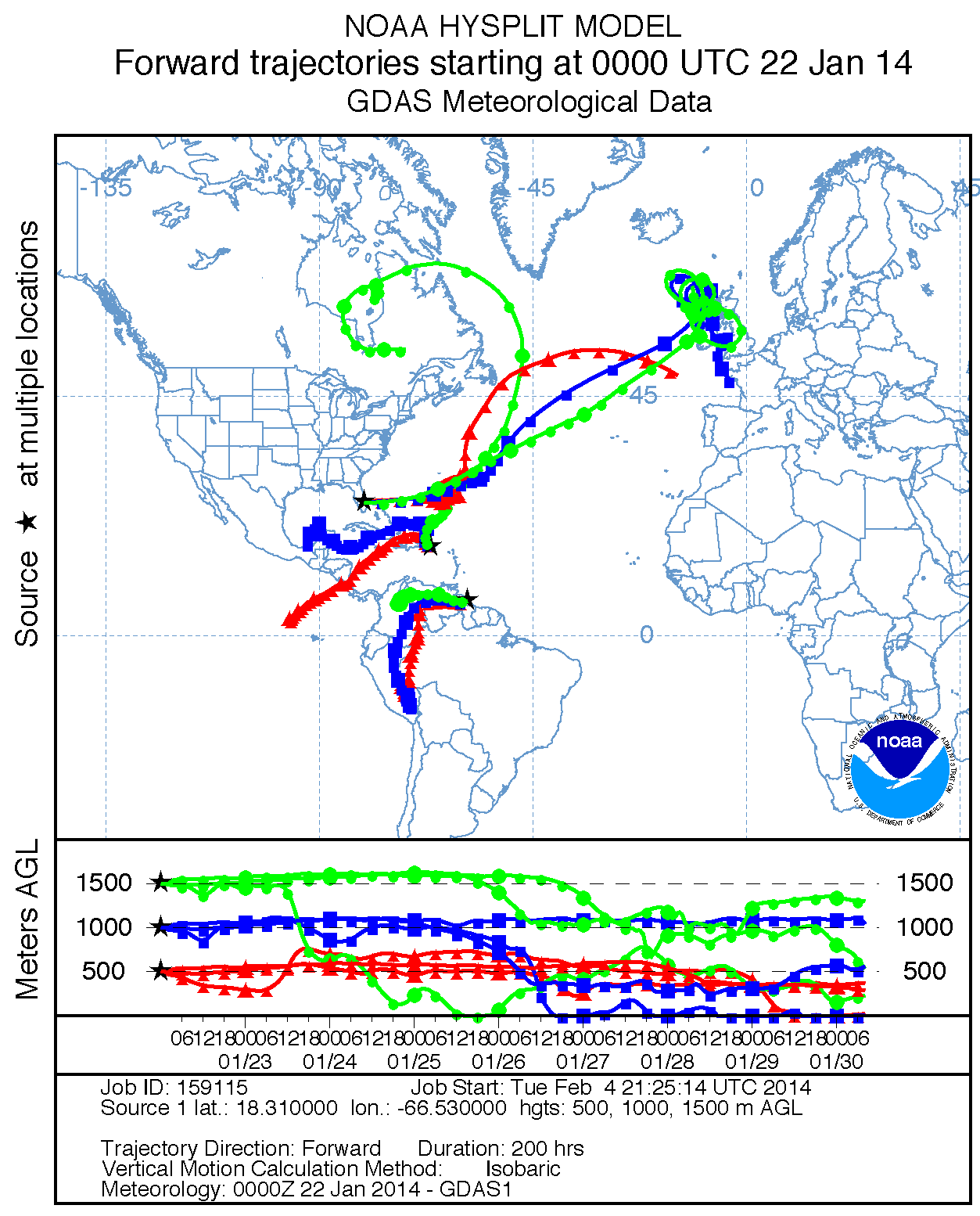

Let’s revisit the movement of air parcels as a potential explanation for such movements. During fall 2012–in the aftermath of the epic passage of Hurricane and Post-tropical cyclone Sandy–BirdCast discussed tracking air parcels as a means to understand patterns of vagrancy. Weekly intervals between early November and the beginning of February show air parcels movements that connect our hypothetical Greater Antilles origin to locations where specimens were found. The imagery below describes the timing of air parcels’ movements and potential outcomes for gallinules. In general, each vagrancy event is associated with an air parcel trajectory for the preceding week, making assumptions about how a Purple Gallinule might fly under such conditions.

Air parcel movements on 1 December were favorable between Florida to Newfoundland, with a nearly direct connection of air 1000 m above the ground, a reasonable height for a gallinule to fly, between the two locations. Even the 500 m and 1500 m heights connect, although both meander substantially west before moving northeast. If a bird departed on this or on a slightly later date, it would experience tailwinds and presumably arrive in Newfoundland in several days. Of course, the precise time of death is unknown.

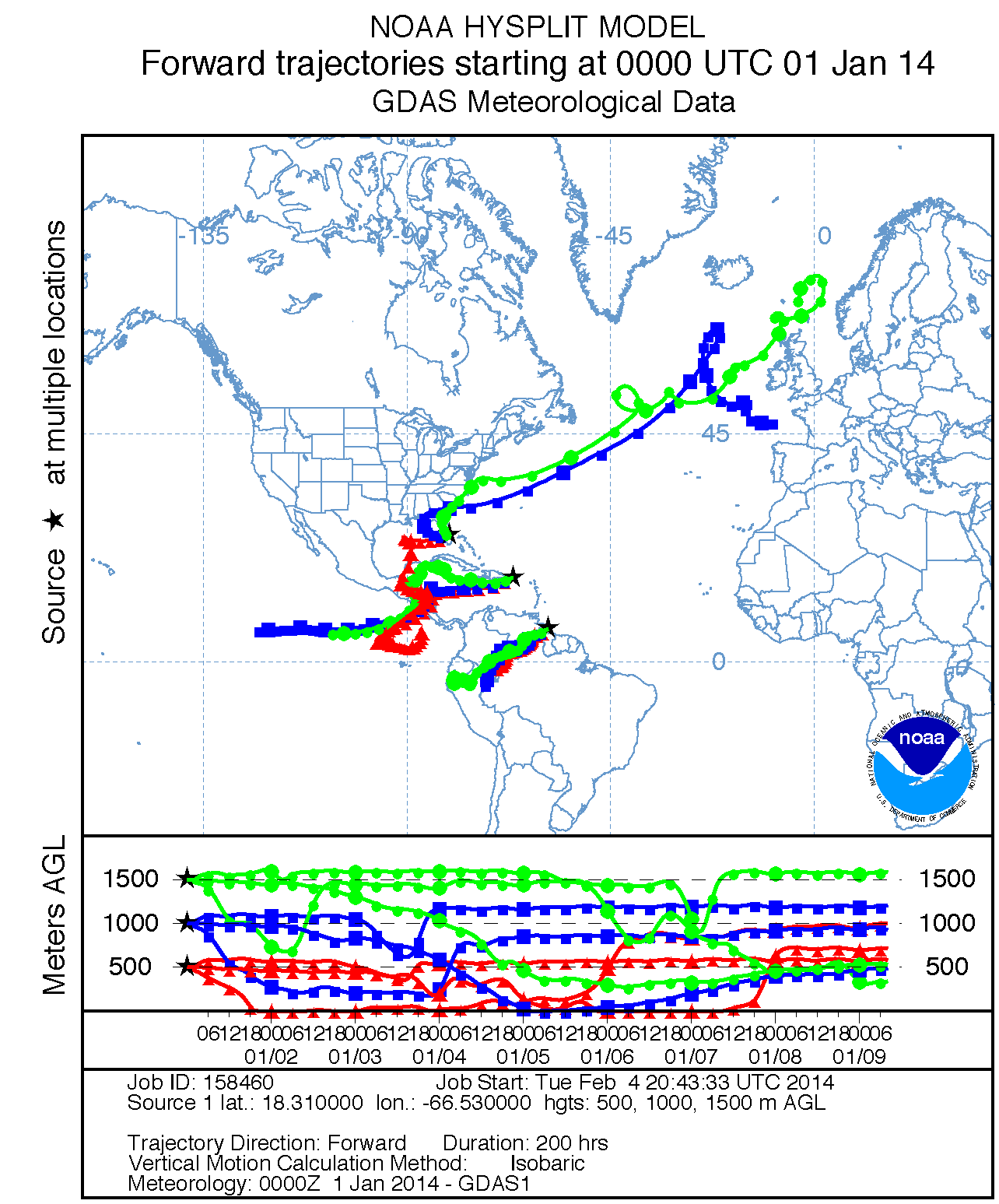

Both of the early January birds were recently dead, so again we consider the week before the records to examine air parcels. Once again we see favorable conditions for transporting gallinules from Florida to New England and Newfoundland, with a nearly direct connection for the movements of air 1000 m and 1500 m above the ground.

The 10 and 13 January birds from Bermuda, which were/are alive, and the 19 January specimen experienced conditions in the week and a half prior to the birds’ discoveries that were favorable for transport. The imagery for 8 January shows higher altitude winds blowing in a favorable direction to move gallinules north up the Atlantic seaboard.

The 15 January imagery shows even more compelling winds (for the specimen record and for the live 21 January Bermuda bird), this time at all altitudes displayed. Furthermore, there is a Caribbean connection as well, with high altitude winds linking an air parcel beginning on Hispanola with the North Atlantic.

Similar conditions existed on 22 January to support movements of gallinules over the ocean to Iceland and Ireland. Perhaps this imagery of air parcel movements more than any other highlights the potential mechanism to facilitate long-distance flights by gallinules. A bird flying downwind or close to it and traveling only 40 kmh could reach Europe within a week.

One take home from all of these air parcel images is that South American origin seems highly unlikely for these Purple Gallinules, given the prevailing winds. Presumed departure points in northeast South America regularly exhibit a pattern of Northeasterly flow–the trade winds–which would not be at all favorable for northward or eastward movement of gallinules.

Another pattern apparent in many of the images show a strong wind flow connection between the central Caribbean and the Caribbean slope of Central America, where wetter than usual conditions presently exist. If some gallinules went south and picked up this wind stream, they may well have been able to reach Central American habitats that could support them. We encourage birders in the Caribbean and Central America to submit their Purple Gallinule observations (on complete checklists, reporting all species, of course) to help us find out!

Water-cooler Fodder

Although this winter’s cold temperatures could yield far-flung Purple Gallinules, evidence this year is stronger for drought driving dispersal from the Caribbean and south Florida. The same systems that have brought extreme cold to the eastern U.S. are also bringing these strong wind fields as the storms spin up the east coast, and this surely has aided the successful trans-Atlantic flights by these gallinules. South America does not seem a likely source, given the prevailing flow of winds in potential source areas for gallinules on that continent. But the origin, motivation, and mechanism of movements are open questions and discussions worth continuing, as we have barely scratched the surface of these patterns. For example, conditions are generally favorable this winter for Nearctic and Neotropical vagrants to reach the Palearctic, with general flow of winds to the east across the Atlantic in the presence of an Azores High, a pattern referred to as positive North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). (As an aside, these conditions and the prevailing trade winds also make for favorable conditions to deposit Palearctic migrants in the Neotropics, a topic we will discuss further in an upcoming post.) NAO phases are cyclic, albeit irregular in their timing and strength. Previous years with strongly positive NAO may well correlate with other instances of North Atlantic vagrancy in this species: if anyone looks into that we’d love to hear back! That would help to answer the question of whether this year is different, whether something fundamental changed, or if Purple Gallinules this year just encountered a perfect combination of drought conditions, positive NAO, and a wobbly polar vortex that is sending numerous strong low pressure systems up the Atlantic Coast. Stay tuned!

————

AF, MJI, CLW