The Florida peninsula draws the eyes of any human scrutinizing a map of North America, and the eyes of millions of birds entering the continent from their tropical haunts each spring. It is uniquely situated to accommodate birds arriving from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean and South America, and the landform hosts a larger suite of wintering Neotropical migrants than any other U.S. state – the result is large numbers of birds funneling up and out of Florida each spring. This is particularly true along Florida’s east coast – a primary conduit and essential presence in the lives of migratory birds that winter in the Caribbean, contrasting with the literal and figurative migration shadow along Florida’s Gulf Coast where prevailing winds and usually dominating high pressure over the Gulf of Mexico frequently send the largest pulses of migrants to arrive in western Gulf of Mexico habitats.

With the exception of western Cuba, the majority of land masses in the Caribbean lie east of the Florida Peninsula, so whether birds fly straight from Trinidad and northern South America or island-hop through the Bahamas or other Greater Antillean islands, Florida represents a critical entry point to continental North America. Yet, whereas birds must cross stretches of open water to reach Florida in the spring, their origins may be significantly closer to Florida arrivals and destinations than the origins of migrants arriving along the western US Gulf of Mexico coast from Mexico and Central America, perhaps the stuff of interesting, future comparisons between trans-Caribbean and trans-Gulf migration. Additionally, prevailing atmospheric conditions make for interesting studies in these areas, with particular patterns easily visible in Florida given its geography – like other north-south oriented land masses, especially peninsulas, east-west wind systems can pin migrants on coast-lines. So in Florida, from Miami to Daytona Beach, birders may be treated to the spectacle of birds arriving from overwater Caribbean flights, and concentrations of birds that have accumulated along the coast line during specific wind conditions.

During the week of April 19-25, several weather events set up excellent conditions for observing visible migration, mostly of wood-warblers, migrating along Florida’s east coast. My colleagues and I were fortunate to be positioned to observe birds’ responses to these weather conditions on a barrier island east of Vero Beach, about the midpoint of the peninsula between Georgia and the Florida Keys and approximately 120 miles from the Bahamas.

Early in the morning of 19 April, a significant frontal boundary that had been slowly working south through the southeastern U.S. passed through central Florida following a period of southwest winds, producing classic conditions for fallout. At first light at Pelican Island NWR (the U.S.’s first national wildlife refuge), there was a light drizzle, with cloud ceiling remaining high and not many birds on the ground. However, a high flight-line of warblers soon became apparent, with flocks of up to 60 birds continuing to move north along the barrier island, in spite of the precipitation. We were unable to get an accurate count as we moved locations to try and get a better vantage point and avoid the increasingly intense precipitation. But once we found shelter, we were amazed to see the stream of warblers continue through even strong downpours. In addition to the major north-south flight lines, some individuals and small groups were also flying in directly from the ocean. This flight continued through the morning, but it seemed that the majority of the birds kept moving, with relatively modest numbers of birds on the ground given the numbers aloft and the wet weather. These checklists illustrate the migration events (S85887474, S85887939, S85916082).

Precipitation and northerly winds persisted for a day after this frontal passage, but the following night of the 20-21 April southwesterly winds return, bringing an influx of birds to the Vero Beach area.

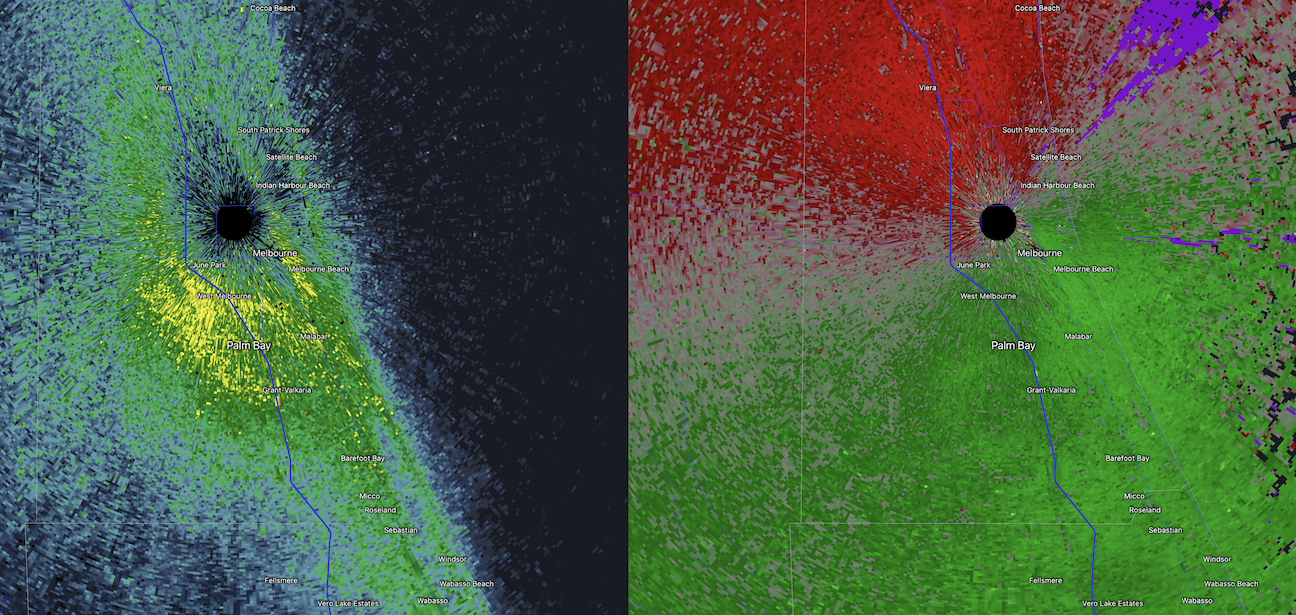

A RadarScope snap shot of 11pm, 20 April 2021, with base reflectivity (left panel) and radial velocity (right panel) showing large (areas of bright yellow) numbers of birds aloft south of the KMLB Melbourne radar (the black dot or “hole”).

Seeking better viewing conditions, we spent the morning of 21 April at Sebastian Inlet State Park, a bulge of land on the barrier island at the south end of an inlet presenting good views of the skies and migrating birds with decisions of where to cross the water and decent stopover habitat. As soon as we arrived, warblers were streaming across the parking lot, low through the vegetation and higher in the sky, with some birds continuing north up the barrier island, some crossing the intracoastal waterway, and others circling back south looking for a place to land. As the morning progressed, it was clear that an increasing proportion of birds were heading inland. While we were unable to keep a comprehensive tally of birds moving, we estimated at least 1600 warblers migrating through the park that day! Improved visibility and more time in the field allowed us to get a better sense of the species composition – almost entirely warblers wintering in the Caribbean region, with Cape May, Black-throated Blue, and Prairie Warblers stealing the show. The South America wintering Blackpoll Warbler was also in evidence, highlighting the connection among this species, the Caribbean and South American components of its passage, and over water flights. The scarcity of Central American winterers like Nashville, Magnolia, and Black-throated Green Warblers, and North American winterers like Yellow-rumped Warblers was suggestive of the origins of the birds observed at this location and date. Other, traditionally Central American migrants from families like flycatchers and some thrushes were conspicuously absent as well. See this checklist (S86030423).

Similar, if not more productive conditions occurred the night of 24-25 April: after several days of northerly winds, floodgates opened with southerly winds earlier on this night, transitioning to more westerly. The result was a massive number of migrants congregated on the barrier islands – in only the first two hours after sunrise on 25 April I tallied 4500 warblers that followed similar flight patterns as those evident on 21 April, only in a greater magnitude! Furthermore, the lower cloud ceiling this morning resulted in birds flying lower, with outstanding and audible flight calling. As the day continued, the northbound flight tapered, but flocks of warblers, bobolinks, and shorebirds continued to arrive from over the ocean, flying at heights near the limit of vision and literally just above the waves. These birds encountered a second frontal boundary that arrived in the afternoon, this time downing the migrants.

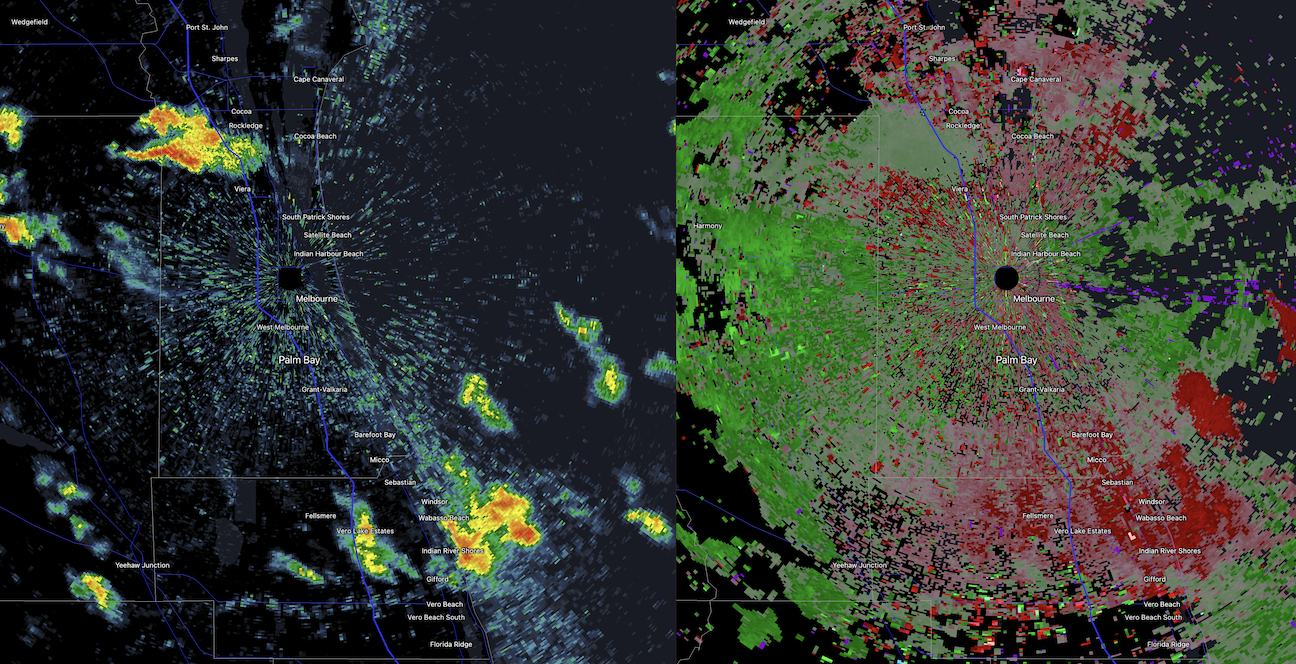

Birds and precipitation are visible in this image, most notably in direct contact to the southeast of the KMLB Melbourne station along the coast. Blocky, irregular patterns of yellow and red illustrate intense precipitation; more lightly stippled greens and blues oriented in parallel to the coast illustrate birds. The storms are moving generally east and southeast, whereas birds are moving generally north or north-northwest. Reflectivity (left), velocity (right).

A short evening walk through a local migrant trap found the habitats teeming with birds. These birds did not stay grounded, however, as local exodus of migrants after sunset was nothing short of massive, despite light headwinds from the northwest.

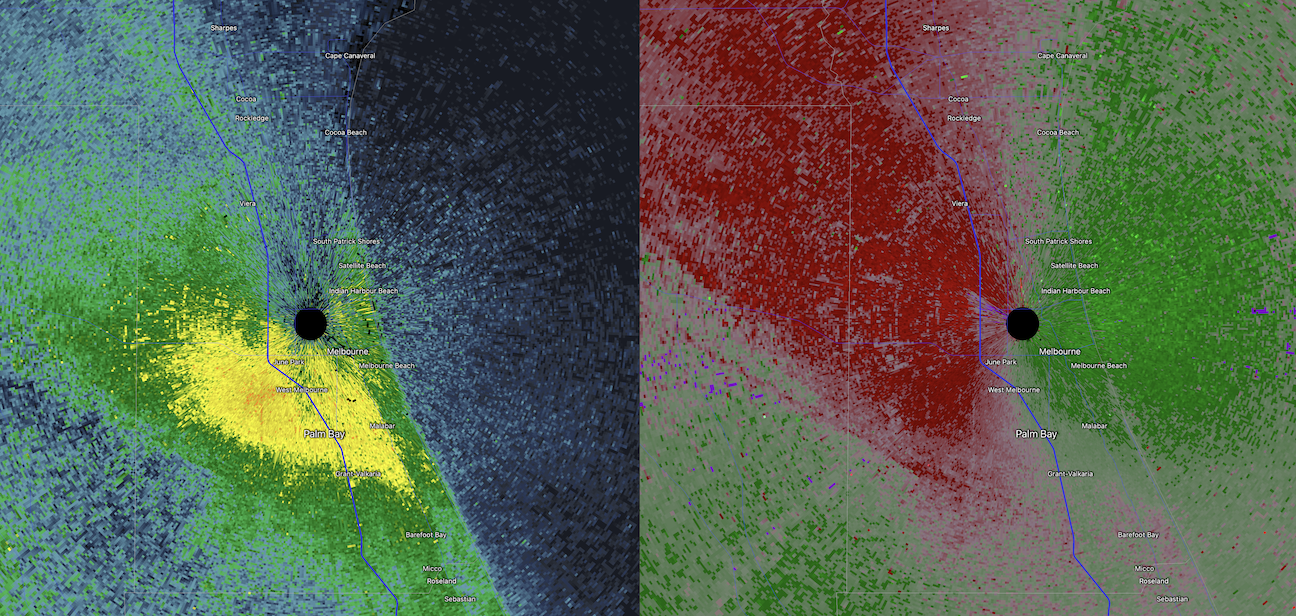

An intense exodus of birds during the evening on 25 April 2021 (11pm ET), with notable concentrations to the south of KMLB Melbourne. Reflectivity (left), velocity (right).

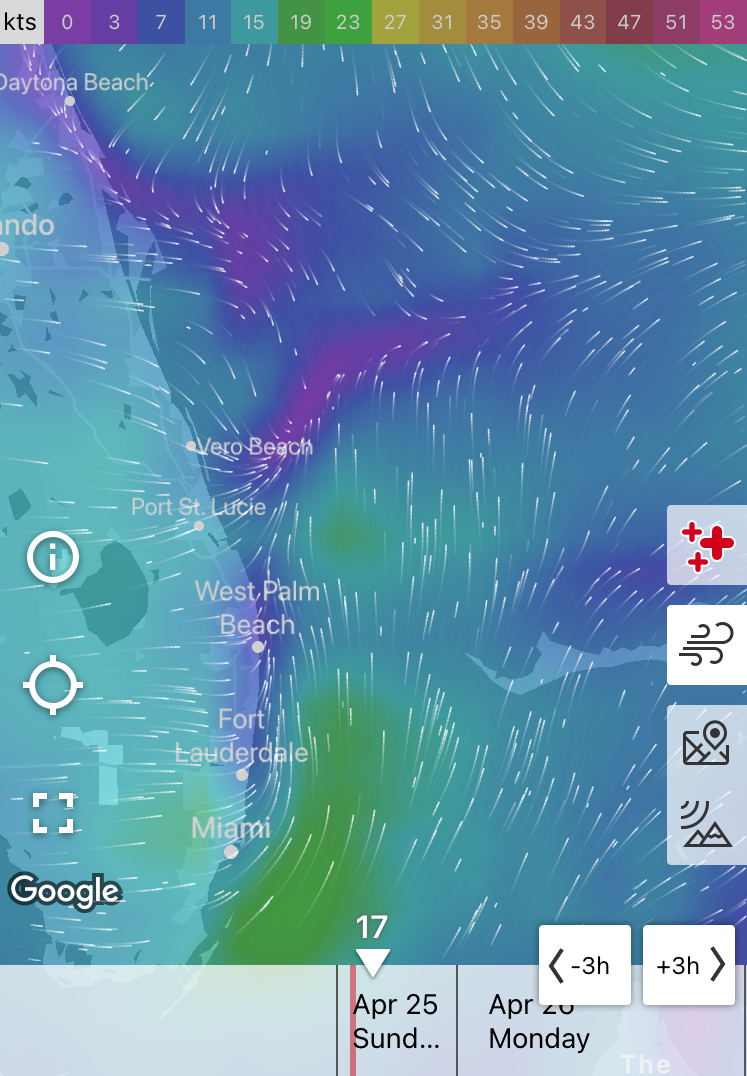

Wind conditions during the evening of 25 April 2021 were marginal for migrants to take flight, but the light headwinds were clearly insufficient to deter many songbirds from engaging in a large exodus event.

For some additional perspective on these flights and the species and numbers of individuals involved, see these checklists (S86317292, S86390110).

While our visit to the area was brief, and veteran Florida birders doubtless have additional invaluable input about these phenomena (check out these lists from a nearby woodlot in a previous year: S68168271, S68148541), it is clear that the east coast of the sunshine state is a unique region for observing spring migration. A systematic migration count in the area would doubtlessly be fruitful. These observations also highlight the importance of preserving stopover habitat, like Pelican Island NWR, Sebastian Inlet State Park, and Captain Forster’s Hammock Preserve, to ensure that these birds have the resources they need to rest and refuel on their arduous journeys.