From March to May, the western and northern coasts of North America’s Gulf of Mexico can host remarkable bird migration events. More than 2 billion birds pass through this region each year (Horton et al. 2019; Cohen et al. 2020), moving from non-breeding and wintering areas in the Caribbean and Central and South American back to their breeding haunts. This spectacle of migration is a well-known phenomenon at many famous Gulf Coast birding sites like South Padre Island, High Island, Grand Isle, Dauphin Island, or Fort Pickens. But how can you know where and when these migration events will happen? With technologies like weather radar, this is easier than ever. Let’s explore how to predict such spring migration events on the Gulf Coast.

Understanding weather conditions that can cause ‘fallouts’

Some of the 2 billion birds that migrate through the Gulf of Mexico region are what are known as “trans-Gulf migrants:” birds that take flight from Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America, and northern South America, and fly for hundreds of kilometers over water. Over the Gulf of Mexico, they are often experiencing very favorable ‘tailwinds’: winds with a generally southerly component that enhance their flights in generally northerly directions.

When south winds blow across the entire Gulf of Mexico and adjacent coasts, the strategy of migrating across water is extremely efficient: these migrants fly over water and cross into the United States, often continuing for up to hundreds of kilometers further inland before landing in the productive habitats of the southern Appalachians or the Mississippi and Ohio River basins.

However, when the winds blow from the south during only parts of their overwater journeys, but then shift to blowing from the north, the situation changes dramatically. This is particularly true if north winds also bring rain and other inclement weather. This combination of a headwind and associated inclement weather causes birds to “fallout”: birds descend quickly and directly (i.e. “fall”) into the nearest habitat rather than flying into highly unfavorable conditions.

The key recipe of birds and weather for Gulf of Mexico fallouts in spring:

- Southerly component to or calm winds (southwest, south, southeast) over the southern half of the Gulf of Mexico, western Caribbean, and northern Central America at sunset

- Northerly component to winds (northwest, north, northeast) and rain over the Gulf of Mexico or adjacent coast the morning following the sunset-time southerly winds

In many ways, it is as simple as this! These conditions generally happen when cold fronts, boundaries between an approaching cool air mass and a receding warm air mass, pass through the Gulf of Mexico region moving eastward, bringing north winds with cooler and drier air that interacts with the warm and moist southerly winds that are typical over the Gulf of Mexico. These boundaries are often unstable, and the weather in their immediate vicinity can be intense, with strong winds and heavy precipitation.

Birding fallout conditions is often better later in the day from the perspective of experiencing fuller extents of birds falling out. Later in the day, usually after mid morning, the faster-flying trans-Gulf migrants arrive first, including shorebirds and waterbirds (generally faster flying and larger bodied birds, so less impacted by winds), followed later in the day by waves of slower flying species. During a fallout condition, this schedule may be delayed by hours or even days, with birds arriving onshore after over water flights at times many hours after their typical arrival windows.

Current forecasts predict these conditions between Wednesday and Saturday this week, 17-20 March 2021. Let’s take a closer look at the forecast and what it might mean for bird migration.

Predictions for 17-20 March 2021

To maximize the number of birds you see from the above list, get as close as possible to Gulf Coast shorelines and watch carefully for birds coming off the water—anywhere from wave height to hundreds of feet over the water. To get used to looking for actively migrating birds, keep an eye out for swallows, as these birds are often the most visible species when these events happen: with shifting winds, insect concentrations increase at the coast, so aerial insectivores like swallows also concentrate by the food source.

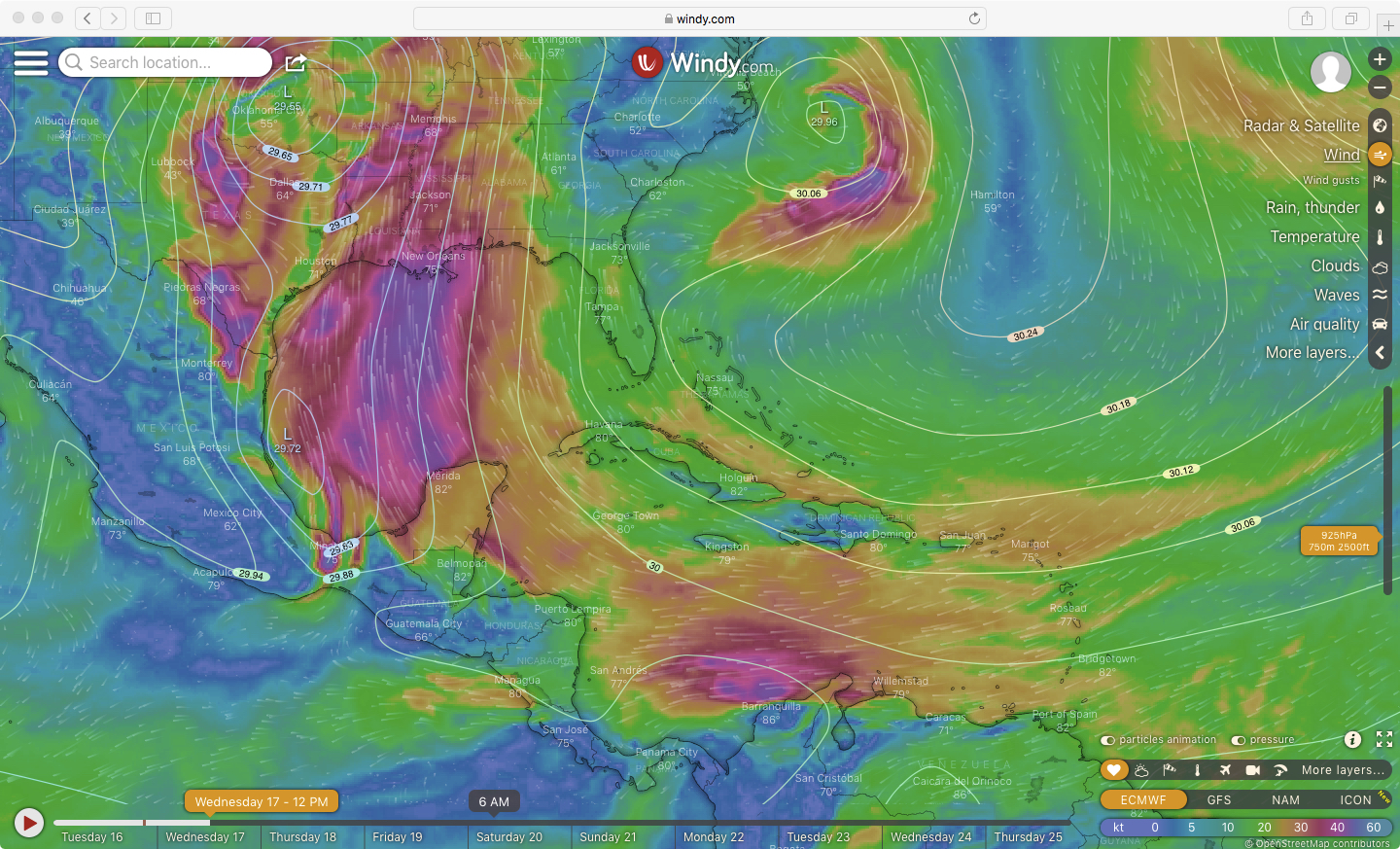

Wednesday 17 March 2021, 11am CDT In this imagery from Windy we see only wind direction and speed and its location relative to isobars (the white lines representing constant pressure). Strong southerly flow over the Gulf of Mexico will facilitate migrating birds. But note the pattern indicative of the approaching frontal boundary, in this image visible as northwesterly flow over Texas. Although birds are not experiencing the unfavorable headwind conditions yet, they will begin to be impacted by the adverse winds once the frontal boundary pushes offshore.

In this imagery from Windy we see only wind direction and speed and its location relative to isobars (the white lines representing constant pressure). Strong southerly flow over the Gulf of Mexico will facilitate migrating birds. But note the pattern indicative of the approaching frontal boundary, in this image visible as northwesterly flow over Texas. Although birds are not experiencing the unfavorable headwind conditions yet, they will begin to be impacted by the adverse winds once the frontal boundary pushes offshore.

Likely fallout timing by regions (local time when birds should start appearing)

- Southern and Central Texas coast (1pm-3pm)

- Upper Texas coast (4pm onward)

- Western and Central Louisiana (4-7pm)

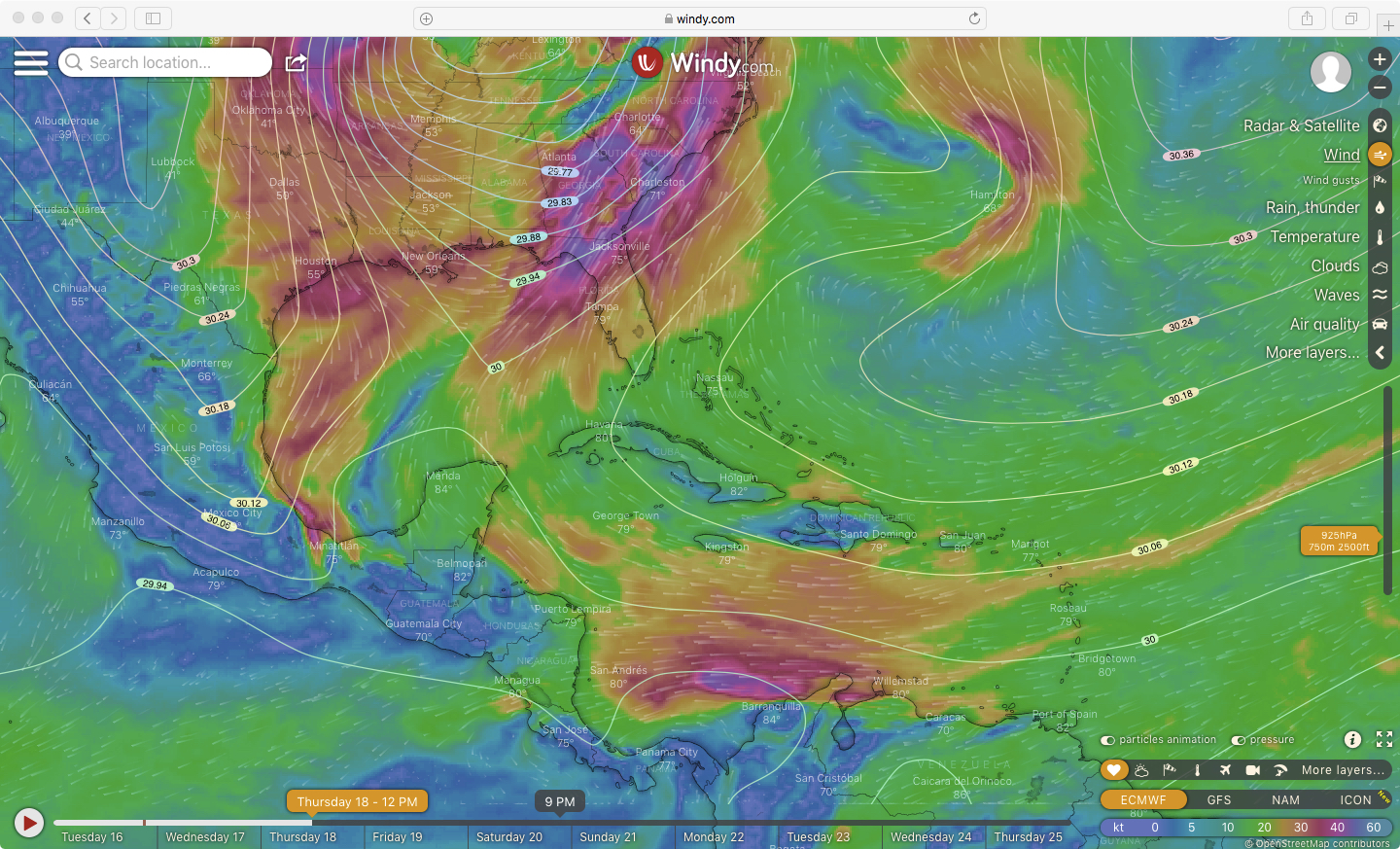

Thursday 18 March 2021, 11am CDT The pattern of winds over the Gulf of Mexico has changed dramatically in this image. Intense southerly flow is occurring in the Florida Panhandle region as well as areas of Georgia, but northerly and northwesterly flow prevails over the central and western Gulf coast areas as well as over portions of the central and western Gulf of Mexico. At this point on Thursday morning, fallout birds have already arrived in Texas, and the potential for fallout conditions in eastern Gulf coast areas and portions of Florida increases dramatically.

The pattern of winds over the Gulf of Mexico has changed dramatically in this image. Intense southerly flow is occurring in the Florida Panhandle region as well as areas of Georgia, but northerly and northwesterly flow prevails over the central and western Gulf coast areas as well as over portions of the central and western Gulf of Mexico. At this point on Thursday morning, fallout birds have already arrived in Texas, and the potential for fallout conditions in eastern Gulf coast areas and portions of Florida increases dramatically.

Likely fallout timing by regions (local time when birds should start appearing)

- Alabama & Mississippi coasts (8am-1pm)

- Florida Panhandle (11am-3pm)

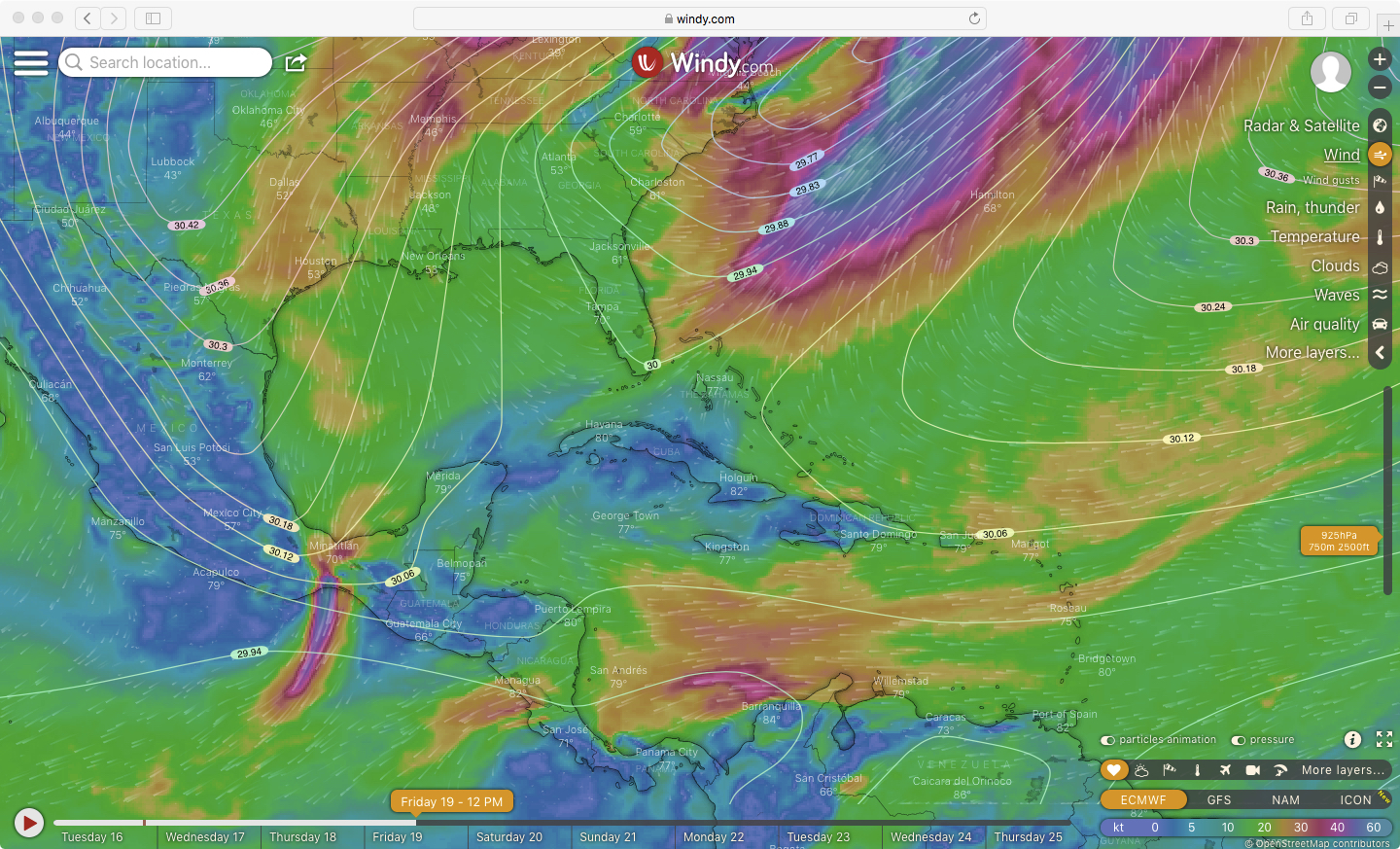

Friday 19 March 2021, 12pm EDT By Friday at 12pm EDT, the frontal boundary has passed Florida, where the last places for fallout potential during this weather event are Southern Florida and the Florida Keys. Northerly flows are prevalent across the Gulf of Mexico and its northern coasts. Additionally, note that conditions for additional departures over the water from points south have now been unfavorable for more than 36 hours.

By Friday at 12pm EDT, the frontal boundary has passed Florida, where the last places for fallout potential during this weather event are Southern Florida and the Florida Keys. Northerly flows are prevalent across the Gulf of Mexico and its northern coasts. Additionally, note that conditions for additional departures over the water from points south have now been unfavorable for more than 36 hours.

Likely fallout timing by regions (local time when birds should start appearing)

- Southern Florida, Florida Keys (6am-10am)

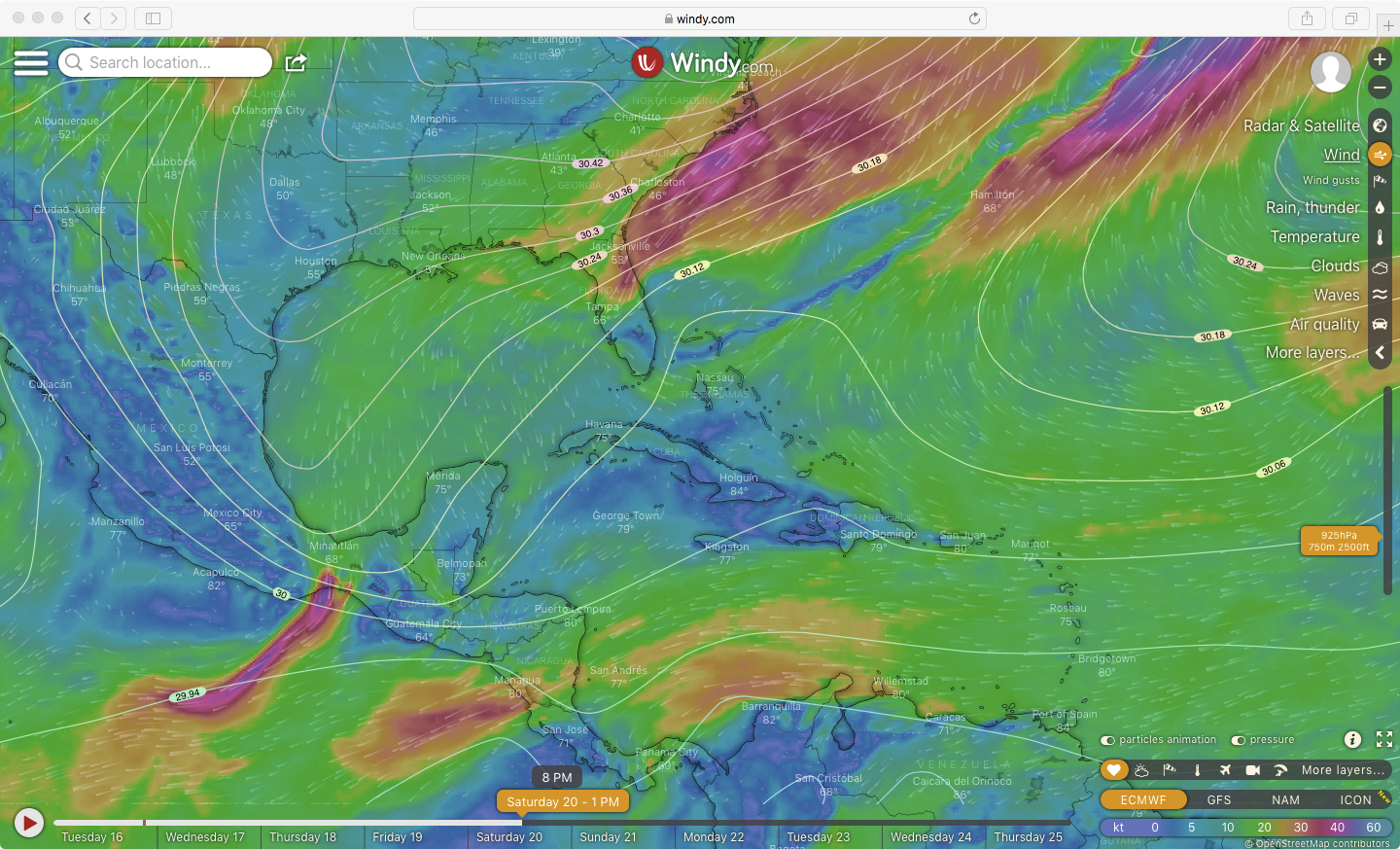

Saturday 20 March 2021, 12pm EDT

On Saturday, the last lingering potential for fallout remains in Florida as birds may arrive into the Florida Keys after departing from points farther south in mostly marginal conditions (i.e. not much supportive tailwind).

Likely fallout timing by regions (time when birds should start appearing)

- Southern Florida, Florida Keys (continuing from previous day)

For some additional insight into the passage of this weather system, note the forecasts for precipitation from midnight Wednesday, 17 March through midnight Saturday, 20 March in the image below (this is a quantitative precipitation forecast, QPF). There are some coastal areas, particularly in the Florida Panhandle and Mississippi River Delta, forecast to receive perhaps a quarter to a half an inch of rain. Note, areas where birds encounter rain in addition to the northerly winds will be more likely to experience fallout conditions, particularly if that rain occurs over the water where birds are flying.

Note that it is quite possible that this frontal system will not develop as predicted, and the entire discussion of birds interacting with precipitation and northerly winds could be moot. But given the current forecasts, the BirdCast team is suggesting an increasing likelihood of interesting and unusual migration events associated with the passage of this system.

Species to watch: Blue-winged Teal, Northern Shoveler, Greater Yellowlegs, Great Blue Heron, Barn Swallow, Northern Rough-winged Swallow, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, Louisiana Waterthrush, Northern Parula

Observations on migration from 17-20 March

In our discussion above, we have been speaking of *predictions* — we think this series of events will happen, but having your sightings to confirm the event is critically valuable. If you are able to safely bird coastal and near-coastal areas over the coming days to report your observations, you can help us collectively better understand these migration events. If you are able to go birding along the Gulf Coast this week, please take detailed notes about the time that you observe any migrants that appear to be associated with changing weather—for example, if you start to see increasing numbers of swallows or migrant flocks of Blue-winged Teal offshore, note the time you see these changes.

We will update this section next week with some of your observations from this migration event, and we can see how well the predictions worked out!

And to add a footnote, possibly a postscript to our predictions, for 19-20 March, birders on the Atlantic Coast should be mindful of the potential for another unusual pattern that may follow the passage of this weather system into the Atlantic Ocean – overshoots by migrants blown offshore, particular off the coast of Florida on Thursday night and early Friday morning during the passage of the frontal system, flying downwind (e.g. flying in strong southerly tailwinds) and appearing far to the north of their intended destinations – we call this a “slingshot” event, and we think such an event may occur for those in northeastern North America (as well as Bermuda).

Have fun, and enjoy spring!