In continuing with our recent string of friends and family posting experiences and stories about bird migration, in particular those that “ground truth” predictions, the BirdCast team opens the forum to Ned Brinkley. We are more than fortunate to have this renaissance man “in residence,” the combination of Ned’s voluminous knowledge of migration with libraries of uncorrelated disciplines conveying a story of migration magic on the coast of Virginia (as it happens there was some magic in northern Virginia, too…). Take it away, Ned!

Saturday, 23 May 2020, dawned like most other May days, full of promise but tempered by the trepidation, endemic to coastal Virginia, that comes from nearly five decades of misinterpreting weather charts in the hope that today will be the day that sees the trees dripping with warblers. Put simply: we just don’t see that in the coastal mid-Atlantic—or, rather, we see it once or twice in a long birding lifetime. Expectations are set low in spring, just as they are justifiably set high in fall, as inexperienced migrants often stack up along the coasts during their first migration. We scrape together very small lists of glorious, singing birds in spring in exchange for Cape-May-like bounties in fall. Like coastal North Carolina, easternmost Virginia lies in a “migration shadow,” too far east of the main migratory pathways to see warbler waves. And my home turf, the southern tip of the Delmarva Peninsula, has the added bonus of being on the wrong side of the nation’s largest estuary, Chesapeake Bay, which northbound nocturnal migrants are loathe to cross.

A careful canvas of my usual litmus-test migrant traps early on 23 May seemed to verify it: even though night winds had started southerly and had shifted westerly halfway through the night, only a smattering of warblers graced woodlands from Cape Charles to Wise Point.

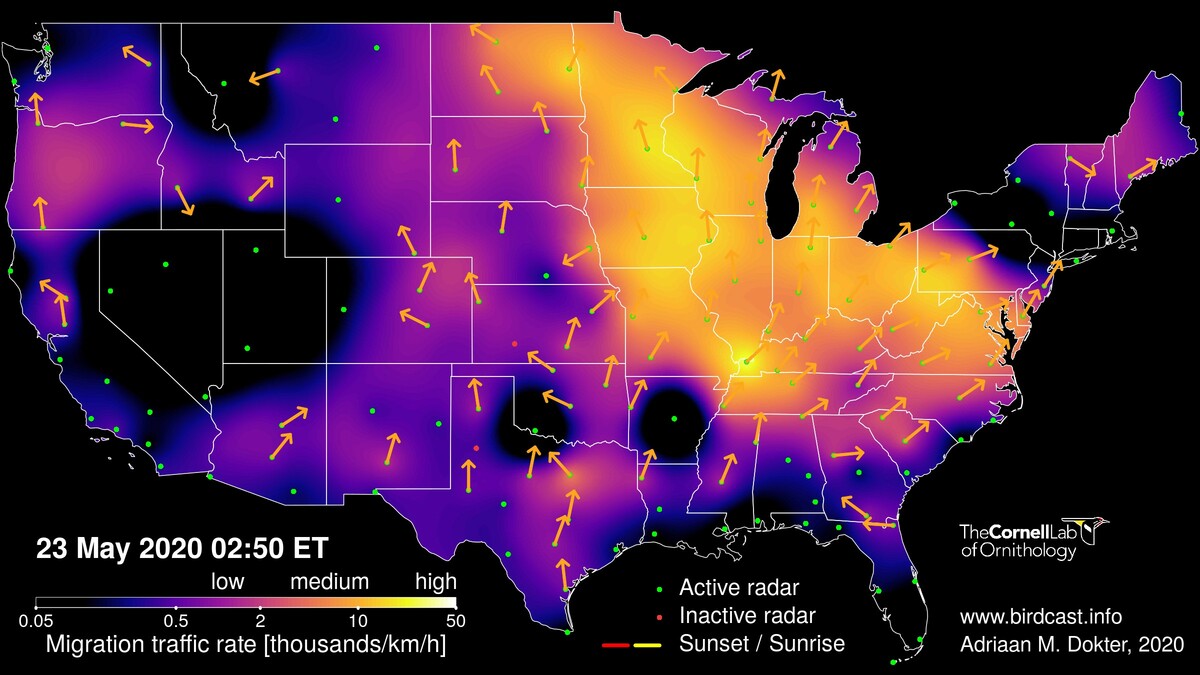

Early morning imagery highlights with arrows directions toward which birds were moving. Notice generally movements toward the northeast, especially in the Carolinas and southern and eastern Virginia. Couple this with imagery from earlier in the evening, highlighting the passage of a strong frontal boundary, and you have the recipe for coastal concentrations.

Across the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, in Virginia Beach, a quick call from Andrew Baldelli reporting a rare Mourning Warbler (typically a migrant found closer to the mountains) put a question mark over the evaluation of “meh” for the migration situation. But by then, lunch was on the horizon, maybe time to put a fork in the migrant assessment for the morning. Perhaps tomorrow would be the day! Lazy, post-middle-aged birding has its privileges. Then another call from Mr. Baldelli. This time with a little more mustard.

To put this in some context: Andrew didn’t just fall off the turnip truck. He came up in the crucible of the take-no-prisoners NYC/Long Island school of birding in the second half of the 1900s—among the likes of Paul Buckley, Tony Lauro, Tom Davis, Tom Burke, and later Shai Mitra and a host of intense birders who watched the weather every day like a shrike watches a vole hole. Virginia, where he settled in 2009, is lucky to have a birder with his dogged determination—seawatching, shorebirding, warblering, Andrew is a man of the field with tremendous acumen, patience, and a sixth-sense for micro-habitats and bird migration, borne of some big victories but also many quiet days. And he knows that you don’t see much at all while sitting at home. The second phone call had a rare tone, a little above his normal baritone: “Hey, uh, you might need to get over here. We just had what sounded like an Alder Flycatcher singing….there’s warblers, Empidonax, birds everywhere….” Like most old-school birding circles, the New York rules are clear: hedge your bets, don’t overplay your hand, and make sure you read the room right before you put down the cards. Understatement and provisional identifications can be hard to parse for the uninitiated, but fortunately, seven years in upstate New York had given me a basic ability to translate, roughly: “Hey. KNUCKLEHEAD. Pay the toll and cross the Bay already, Alder Flycatcher and birds dripping off the trees. Get over here.” (A singing Alder Flycatcher on the Virginia coast was, at this point, mythical to me. No one has ever reported one.)

I skipped the meal, and regrettably the deodorant, put on boots that I did not lace, and went zipping south in the 20-year-old Corolla with the steering wheel that shakes like Linda Blair in The Exorcist if I go faster than 30. The phrase “bird bum” passed through my thoughts as I parted with $18 to drive as many miles over the bridge-tunnel to Virginia Beach (or “Gomorrah” as we rural people call it). I groped around the back seat for a ball cap, realizing my coronavirus/red-wine homemade haircut might alarm civilized people. Arriving at the lush Tidewater Arboretum, a spring site pioneered by Andrew, I see a few birders in the distance. Andrew has been using the morning to re-locate the Mourning Warbler for each arriving group, and by now, it’s noon. He’s already put in a half day, using the time to teach people about birds as he tries to tally the migrants. The birds are indeed dripping off the trees in the Virginia Tech Hampton Roads Bayscape Garden: I enter the dreamscape.

More perspective: the last time I saw spring birds like this in this corner of the state was over 40 years ago. (True, in May 2001, we had a fallout on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, but not so much on dry land.) I was a teenager the last time I saw something like this on a foggy morning. I’m 55 now, arriving late to the party but ready to rumble. And even at noon, the birding didn’t start slowly. Three Swainson’s Thrushes foraged like barnyard chickens in a heap of mulch while three or more sang loudly off-stage. Each tree seemed to have three or four Blackpoll Warblers and two or three American Redstarts, with young birds and females outnumbering adult males. Magnolia Warblers called and zipped around like they were no big deal (in most spring seasons, an avid birder might see three or four here). And the species list grew every time we picked up binoculars: Ovenbird, Black-throated Green, Black-throated Blue, Yellow, Myrtle (what? 23 May?), Northern Parula. And plenty of Red-eyed Vireos, Common Yellowthroats, and Gray Catbirds behaving like restless migrants rather than locals. Then Andrew said: we should go check the flycatchers. (I’m thinking, “yeah, Empidonax in spring? I have to see it to believe it.”)

We walked into the arboretum proper. The flycatchers started fluttering off the trees. Willows, to judge by plumage—no, wait, Willows by call. Then a bird that looked mighty like an Alder. By now, Andrew was overdue for family commitments, but Tommy Maloney and I kept going, slowly northward, and each tree seemed to have an Empidonax, mostly Willow, a few Acadian, a Least. At the duck pond, the scrubby trees trembled with movement. And with song: first Willows singing, then one, two, three Alder Flycatchers in song. “WTF,” my mind keeps repeating (uh, that’s what young people use to mean “what’s this flycatcher?”). Text messages fly, but by now almost everyone is at backyard cookouts or other Memorial Day weekend events. And the hits keep coming: Bay-breasted, Chestnut-sided, Hooded, Canada, another Mourning. We can’t find the Blue-winged Warbler or Northern Waterthrush from earlier in the day, but Scarlet Tanagers, Veeries, a late (?) Wood Thrush, and a steady parade of wood-pewees keep binoculars in constant motion.

The day ended in the exhaustion familiar to birders specifically obsessed with migration. The total? Just over 200 migrants in a 10-acre patch. A paltry number, you might say—just one tree at Point Pelee may hold more. That’s true. But gamblers who try hard, and lose a lot, tend to appreciate the rare win all the more. Birding is a pastime in which the joy you experience isn’t necessarily measured in the degree of rarity, the numbers you see, or even the views you get. You either feel it or you don’t. On 23 May, Andrew made the prediction, sounded the alarm, and the people came—socially distanced, you bet, but bound close by a bird fallout in a beautiful setting, on a lovely warm spring day, a banquet that he had been working on for a decade. Hats off, buddy. You can read a weather chart with the best of them. We owe ya. (Oh, and also for the five days prior, when you had us out seawatching during Tropical Storm Arthur, which was probably responsible for backing up and belating all the migrating passerines in the first place.) What a day. What a week!

Ned Brinkley