The BirdCast team loves a report from the field, and today we have one from Colorado – the home of our western base of operations, Colorado State University, where Dr. Kyle Horton directs the AeroEco Lab. We are especially pleased to introduce Mikko Jimenez, a PhD student in the Lab, to describe his experiences with the amazing and cool BirdScan MR1, a compact radar for monitoring the atmosphere (bird migration in particular, of course!) at resolutions far finer than those we typically discuss for WSR-88D operations. Take it away, Mikko!

Photo of Mikko Jimenez setting up the BirdScan MR1 radar for data collection. Photo taken by Annika Abbott.

It’s 9 p.m. and I’m settling into my camping chair in the middle of Pawnee National Grassland in central Colorado. My research assistant, Annika, and I have just set up our tents and I’m heating up water for hot chocolate. The sun set just over an hour ago and we are starting to get a glimpse of the stars.

But while we are winding down, the monitor sitting in the bed of our truck is showing that the thing we’ve come here to study is just beginning to pick up: a steady stream of birds is beginning to migrate over us.

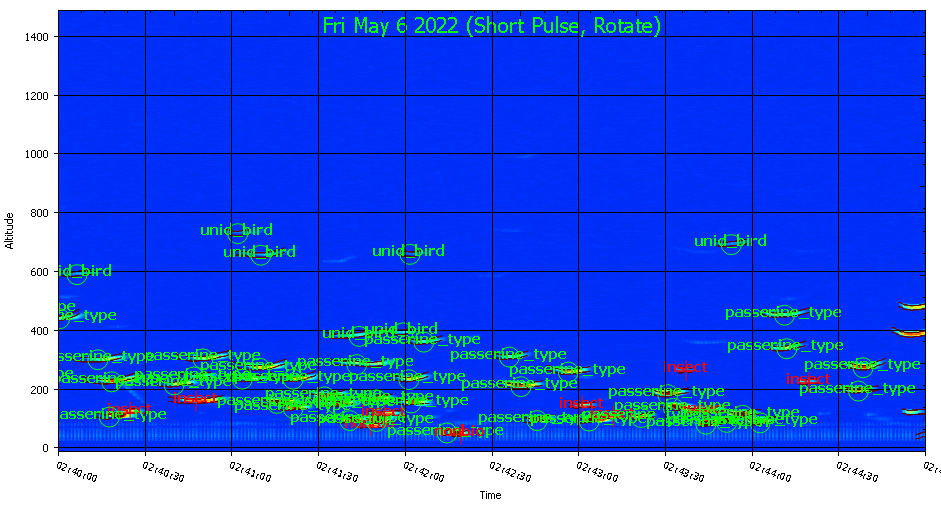

The monitor is attached to the BirdScan MR1, a mobile radar designed specifically to quantify the movement of animals in the aerospace. The BirdScan collects data on what is moving through the aerospace and classifies detections as specific categories of birds (such as waders, passerines, swifts, etc.) based on the amount of reflectivity and wingbeat patterns of each reading. While we are using it to study bird migration, we regularly detect other flying animals, such as insects. It’s an incredible piece of equipment – the only one in North America.

A sample screenshot from the BirdScan MR1 radar, showing detections of birds up to approximately 800 meters above the radar. Each symbol and label represents an individual flying target, whether a bird (green circles with labels) or an insect (red plus with labels). In this image most birds are passerines, likely small to medium sized songbirds.

For nearly two months, we have been collecting data on the number of birds that migrate over different areas of Colorado. Our sites span two transects: one that runs southeast from Cheyenne, WY into the relatively flat plains of central Colorado and one that runs southwest through the foothills, ending near Rocky Mountain National Park. By collecting migration passage rates at varying distances and elevations from the NEXRAD site in Cheyenne, our hope is to ground truth the data collected by that stationary weather radar. As a PhD student at Colorado State University looking to better understand where and when birds migrate, I’m hoping to integrate these data into one of my dissertation chapters. But, more importantly, our findings potentially have implications for BirdCast as a whole: if we understand how distance and elevation gradients bias data collection, we can better correct for them to extend and improve migration forecasts, which rely on data from the whole NEXRAD system.

Timelapse of Mikko Jimenez and Annika Abbott operating the BirdScan MR1 in Pawnee Grassland. Photos taken by Mikko Jimenez.

The BirdScan MR1 (affectionately dubbed “Scanley Hudson”) does most of the work. Our time is largely spent watching the data come in. As we watch, I often find myself thinking about two things that don’t immediately seem connected: grasslands and darkness. Spending my days driving across central Colorado, I’ve really fallen for the short-grass prairie. Everyone fawns over the mountains in the western part of the state, but watching the pronghorn graze in the distance, surrounded by singing Western Meadowlarks and Lark Buntings, it feels you can catch a glimpse of what the American west might’ve once looked like. Once the sun sets, the darkness sets in, and the skies are absolutely breathtaking. As someone who has spent the bulk of my life in cities, true dark nights are new to me. I am repeatedly blown away by the number of stars we see in central Colorado. I even saw the Milky Way for the first time just a couple weeks ago.

But these two things are related in a rather unfortunate way. Both grasslands and dark night skies are disappearing at a rapid pace. Grassland birds are some of the fastest declining species on the planet due in large part to receding prairies. Likewise, while we don’t generally think about the night sky as a habitat under threat, the light pollution associated with human development has drastically altered the landscape. You can actually see the skyglow from the front range more than 70 miles away when you look west from central Colorado at night. Like the grassland itself, we are losing darkness. Both losses have huge implications for migrating birds: many birds depend on grasslands to stopover or breed, and we know that anthropogenic light at night is closely tied to birds colliding with buildings and other human-built structures.

As the pot of water begins to boil, I’m brought back to the task of making hot chocolate. I take the water off the stove and pour two cups. I take mine and walk away from the truck, into the darkness. I can tell the migration activity is picking up because I can hear faint flight calls from the birds migrating above us. I’m excited about the science that we’re doing. If we know where and when birds are migrating, we have a better shot at figuring out ways to protect them. We can be more strategic about saving and restoring critical habitat. We can reduce the amount of light pollution during peak migration. The data we’re collecting can help us take action. But science also has its limits. It’s one thing to see dots on a screen and think about research questions. It’s quite another to completely lose yourself in the night sky and hear the birds flying overhead.

As birders, we typically experience spring migration in the form of early mornings, scanning trees and picking apart dawn choruses in search of new arrivals. But our spectacle is merely the aftermath. The bulk of the migration action is happening while we are asleep. This field season has been a reminder of that, and that the landscape birds are migrating across is constantly changing in various ways.

A photo of the BirdScan MR1 and the night sky in Pawnee National Grassland. Photo taken by Kyle Horton.

Mikko Jimenez is a PhD student in the AeroEco lab at Colorado State University, where he studies the intersection of bird migration and urban life. He has written for The National Audubon Society, Nature Portfolio, and Positively Filipino. Follow him on Twitter @MikkoJimenez.