A migrating White-breasted Nuthatch in Cape May, NJ. Andrew Dreelin/Macaulay Library. eBird S51618256.

Yes, you read the title correctly — WHITE-breasted Nuthatches! Long overlooked as a humble resident of forests and feeders across North America, the *other* migrating nuthatch is finally getting deserved recognition for its irruptive travels.

Word is out that fall 2020 represents another exciting irruption year for Red-breasted Nuthatches and Purple Finches among other species across eastern North America. These “irruptions” occur when species that are facultative (that is species that migrate when conditions necessitate such movements) migrants move in large numbers in seemingly irregular patterns, often in response to inconsistent food resources that vary depending on the year (Newton 2012). Many North American species are facultative and irrupt in cyclical patterns, like boreal finches in response to seed crops and raptors like Northern Saw-whet Owls and Northern Goshawks in response to rodent abundance. Demographic growth of such populations on their breeding grounds after a productive year also contributes to birds’ irruptions as they disperse in response to increased competition for resources (Ehrlich et al. 1988).

Just nine days after BirdCast commented on the current Red-breasted Nuthatch irruption, the Cape May Bird Observatory set a new record for August Red-breasted Nuthatches and the same day at least one was seen as far south as coastal Virginia. While many birders are thrilled to add this species to their local year lists, we tend to overlook its more familiar and widespread cousin, the White-breasted Nuthatch. Field guides to birds of North America show the eastern half of the White-breasted Nuthatch’s range map colored purple to indicate residency, with little mention of irruptive tendencies. Boring, right?

Are White-breasted Nuthatches irruptive migrants, too?

Although known to some ornithologists and coastal birders for decades, fall 2018 was an irruption year in eastern North America that brought White-breasted Nuthatch migration to the attention of many. Observant birders documented White-breasted Nuthatches flying through the crisp fall air at coastal migration hotspots like Cape May, NJ, Long Island, NY, and along the shores of the Great Lakes, and also inland at locations like Merrill Creek Reservoir, NJ. This even includes sightings of White-breasted Nuthatches blown miles out to sea off the tip of Montauk Point, NY and fighting against the wind to return to land or birds coming in off the ocean and just getting back to the beach at the Avalon Seawatch in NJ. While offshore sightings are more frequent for known migrants like warblers, it’s certainly a strange place to see a favorite of backyard feeders!

The sight of these hefty nuthatches barreling through the blue sky with their gleaming white bellies set off a flurry of discussion among birders on social media and inspired us to look deeper into the story of White-breasted Nuthatch migration.

White-breasted Nuthatch in flight. Andrew Dreelin/Macaulay Library. eBird S49379663.

Searching through eBird’s vast archive of bird observations (and documentation), we found some examples from additional areas that highlight the irruptive character of this species. The Canadian Maritime provinces are well known for their many vagrants and fall outs, particularly in Nova Scotia. It may also be a popular flyway for the White-breasted Nuthatch, so trendy that Clarence Stevens Sr in Lunenburg got tired of counting a fallout of nuthatches coming in to land from the sea in October 2016!

Another clue that can identify irruptive movements is that birds disperse in multiple directions rather than just south, so much so that some birds might actually go north from their northernmost breeding grounds! We found an example from far northwestern Quebec, where Hilde Marie Johansen and Alexandre Anctil had the first county record of a White-breasted Nuthatch visit their backyard from October 2016 to January 2017. Fall 2016 was also an irruption year for Red-breasted Nuthatches, another example of an irruption year coinciding with White-breasted Nuthatch movement.

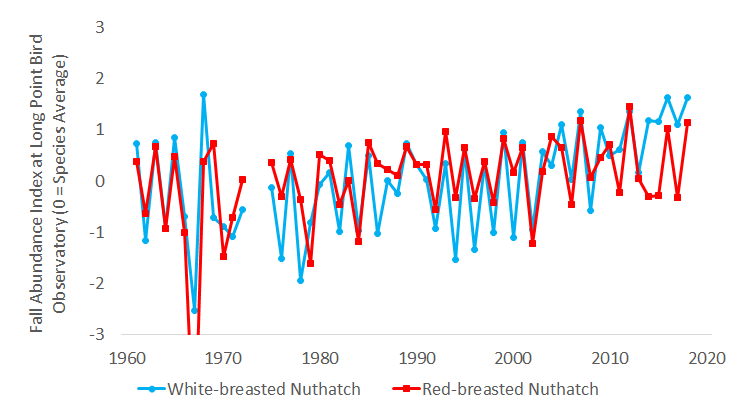

Looking at count data from Bird Observatories at migration hotspots, a pattern quickly emerges— the White-breasted Nuthatch movement tends to occur the same year as irruptions of Red-breasted Nuthatches. These comparisons would be impossible without long-term migration monitoring data from Bird Observatories such as Long Point in Ontario, which has carefully tracked migratory nuthatch abundance since the early 1960s.

Each unit change in fall season Long Point abundance index indicates a change of one standard deviation in the local population estimate based on data from banding captures and sightings of free-moving birds.

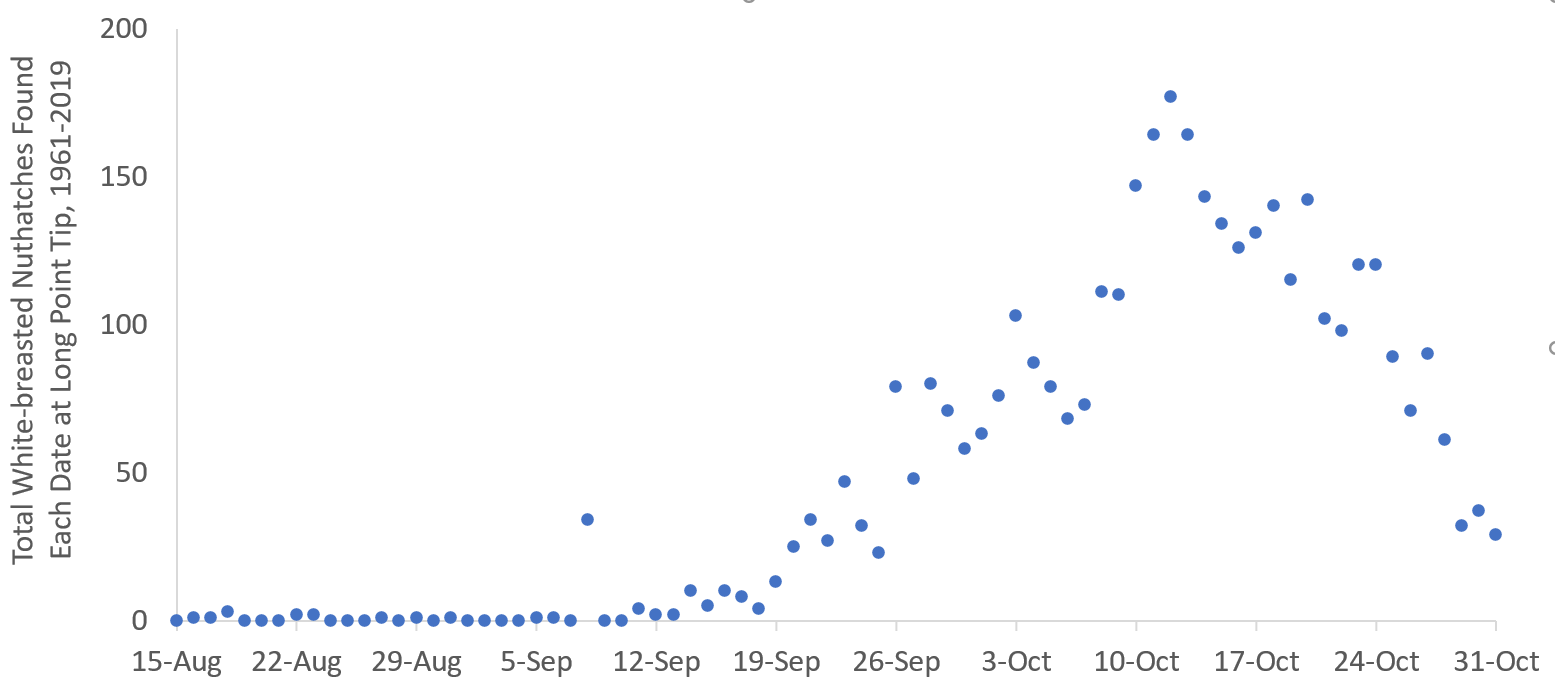

When do the birds move? At Long Point Bird Observatory’s banding station on the tip of the peninsula, White-breasted Nuthatch flights increase in frequency from mid-September until mid-October:

Aggregated total across all years of the total number of White-breasted Nuthatches found at Long Point tip on each date. At a specific site where very few spend the summer, many are detected in fall migration.

White-breasted Nuthatch abundance also occurs in the same approximately every-other-year pattern and also peaks in October at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania, at Cape May Bird Observatory Morning Flight count in New Jersey, and at various eBird hotspots in the Mid-Atlantic region.

Could White-breasted Nuthatches be cueing into some of the same food resources as other irruptive species like boreal finches, Blue Jays, and Red-breasted Nuthatches departing from the northern breeding grounds based on food availability (Strong et al. 2015)? If key trees and shrubs produce abundant seed yields during “mast years,” then the birds can stay in place and avoid the stress and danger of migration. But when times of scarce resources coincide with relatively high populations, irruptions occur.

Witnessing migrating nuthatches

We believe that White-breasted Nuthatches and other “resident” species of eastern deciduous forest can be irruptive, but these irruptions are overlooked because most birds move around within their annual range and thus appear unremarkable, blending in with the locals. However, there are a few hints you might look for that could indicate an irruption is in progress.

- If you see a sudden increase in abundance at a place where you’ve been birding regularly for the whole summer, especially if those surges occur in September and October, that’s a clue.

- If you keep your eyes up, you might see birds flying southbound in the fall or northbound in the spring. While local birds can fly any direction, migrants often fly quite high above the treetops and stick to a long straight course in the expected migratory direction.

For example, in this checklist by Stephanie Seymour from October 2018, she reported highflying southbound White-breasted Nuthatches and Red-bellied Woodpeckers over her yard, incredulous that these so-called resident species were so clearly migrating before her eyes! Migration like this happens all across the landscape, but the chances on any given day are best along coastlines where migration is strong and nuthatches less abundant. Birding hotspots like Cape May and Long Point are ideal, but other geographical features that acts as a “leading line” to funnel migrating birds will do, such as mountain ridges, river corridors, or any notable water boundary.

We hope more birders take pleasure in recognizing a new behavior in a familiar species this season. We still have much to learn about irruptive movements in North American birds, especially in the western US, where complex topography, mountain ranges, microclimates and varied ecosystems make investigations much more challenging. Wherever you are, you can help us learn more about irruptive species, including White-breasted Nuthatch, by submitting your observations to eBird.

Fortunately we have a golden opportunity with the 2020 irruption to push our knowledge forward. We’ve already had our first big sign that a White-breasted Nuthatch irruption is happening again in the east this year. Martha Bromby counted 21 White-breasted Nuthatches described as migrating along with 100 Black-capped Chickadees and some neotropical songbirds along the shore of Lac Saint-Pierre in Québec on September 6th. Together with a few smaller anecdotes, we believe “White-breasted Nuthatch irruption is on!” Get out there and watch your nuthatches closely!

About the authors

Andrew Dreelin is a first-year graduate student in the Jones Evidence-based Restoration Lab at Northern Illinois University where he studies grassland bird interactions with Black-tailed Prairie Dogs in Montana.

Paul Heveran is a volunteer counter at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary and an undergraduate student at DeSales University, majoring in Biology but especially interested in studying bird migration.

Ricky Dunn has acted as a science advisor to the Canadian Migration Monitoring Network since her retirement from Environment Canada, and happily plays with citizen science data at every opportunity.

Andra Florea is a bird bander at Tadoussac Bird Observatory and a master’s student in Oceanography at University of Québec in Rimouski where she is working to develop a sustainable scallop fishery in Sanikiluaq, Nunavut.

Joe Gyekis is a health science teacher at Penn State University and a birder interested in finding something unexpected, whether that be a vagrant, an odd chirp, or an unfamiliar behavior.

Acknowledgements

We owe a big thank you to the BirdCast team for their helpful feedback in shaping this blog post and for the opportunity to publish this piece in the first place!

References

Ehrlich, P.R., Dobkin, D.S. & Wheye, D. (1988). Irruptions. Accessed September 2020. https://stanford.io/3hk6dm4

Long Point Bird Observatory (2020). Canadian Migration Monitoring Network – Abundance Index. Accessed May 2020. https://www.birdscanada.org/birdmon/default/popindices.jsp?what=about

Newton, I. (2012). Obligate and facultative migration in birds: ecological aspects. Journal of Ornithology, 153 (sup. 1). 171-180.

Potter, D. & M. Obbard. (2017). Ontario wildlife food survey, 2016. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Science and Research Branch, Peterborough, Ontario. Science and Research Technical Report TR-18. 64 pp.

Strong, C., Zuckerberg, B., Betancourt, J. L., & Koenig, W. D. (2015). Climatic dipoles drive two principal modes of North American boreal bird irruption. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(21), E2795-E2802.